One Way Smart Developers Make Bad Strategic Decisions

We’re Earthly. We make building software simpler and faster using containerization. Struggling with standardization? Earthly can help streamline your build processes and CI/CD pipelines. Check us out.

Sometimes smart people working hard make things worse. The following story is based my recollection of some real events:

Scheduling Work Problems

A small team of developers at a mid-sized SaaS company has a problem. They own several services that do some data loading and transforming. And the services are under increased load because a new customer (Customer-A) is generating many times the amount of data that most customers do.

They manage to get that under control, but a second problem occurs. They’ve increased the data processing through-put, but it turns out they’ve hurt its fairness. As a result, some other customers are often waiting or getting stale results. Customer-A is clogging up the work queue and starving other customers out. The problem is like an operating system scheduling problem but in a micro-services, distributed system context.

And this is causing the worst kind of problems: people problems – the kind of problem where an executive who didn’t know that a service existed is now requesting daily updates on it.

It turns out this service is using a Postgres table and Kafka topics for scheduling. And there are lots of variables to tweak to get the right combination of through-put and fairness. Scheduling is hard. So calls go out: who can help with this system? Other developers in the company who do similar work aren’t familiar with Kafka. It’s best to let the people who know the system work to improve it.

So the team finds a compromise between fairness and through-put - but to prevent further incidents, Tim gets asked to investigate how queuing and work-in-progress are handled among the company’s hundred-plus services.

Tim is a very senior technical lead, and he’s good at his job. The problem put to him is: how do we make sure this doesn’t happen again? We are expecting N more customers the size of Customer-A, and we can’t afford to learn this lesson one incident at a time, as one service after another learns to keep up with increased work. If we do that, we’ll lose high profile customers, and something something shareholder value. We need a better solution than that.

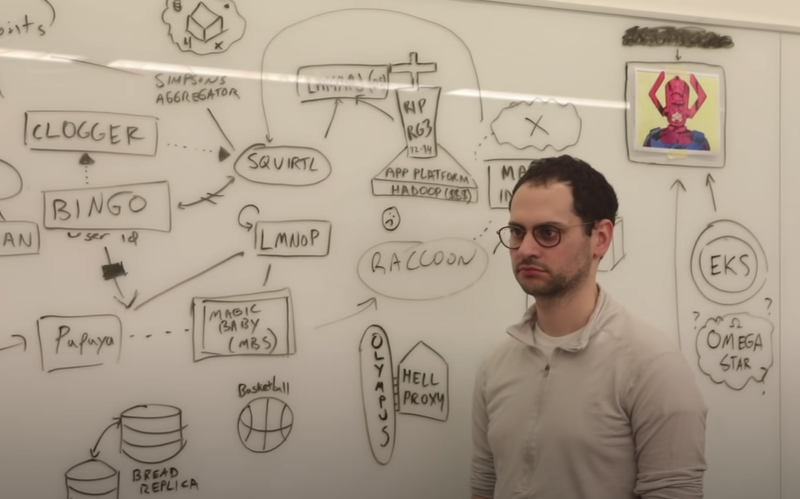

So Tim studies all the existing services and starts mapping things out. It turns out that, across all the services, queuing, and work in progress are handled in every possible way. It’s hard for him to get a truly global view of everything, but it looks like most services are using SQS, database tables, or Kafka.

A Solution

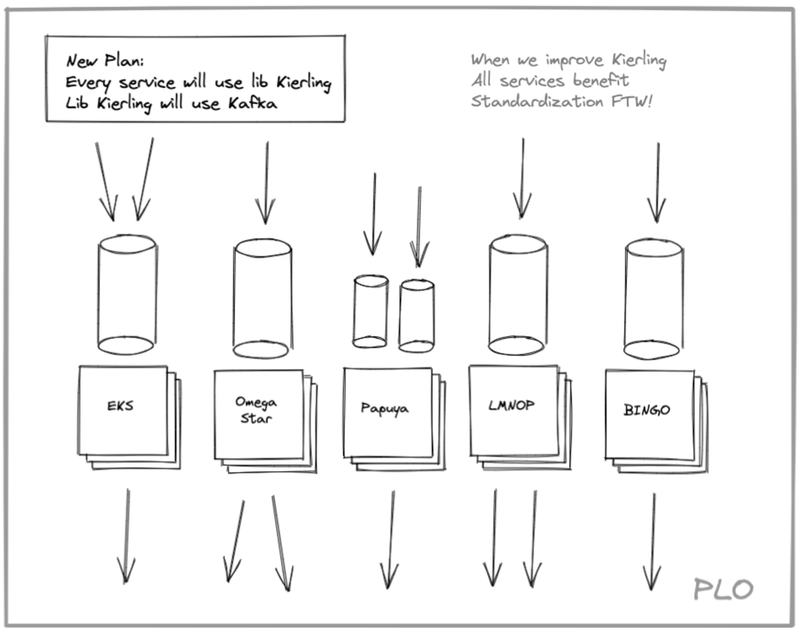

So Tim proposes a solution. They would create a shared library, which you can use for all your queuing and message processing needs. It will be backed by Kafka, and everybody will move to it.

The beauty of this solution is that everything will work the same. If one team working on one service solves some work-starving problem, others can use the solution, because it’s a shared lib. And if things go wrong in one area, people from other teams can lend a hand, because its all the same solution everywhere.

Well it didn’t work out like that at all.

How Things Failed

In the old world, every service that processed data was doing things slightly differently, which made the system as a whole hard to understand from a top-down perspective. Tim had a hard time wrapping his head around how everything worked, and also some of these various subsystems had problems that would only get worse at scale.

The hypothesis was that by standardizing things many of these little unrelated problems, including the initial fairness problem, could be solved all at once. But, that hypothesis turned out to be wrong. Standardizing was a considerable effort that solved some problems but overall it made things work less well. And it turns out that there is a great book written all about this type of error.

Side Note: Kafka

I think picking Kafka was a tactical error here because it’s a bad fit for being a work queue, and Kafka has a big learning curve. But there were uninteresting, extenuating circumstances that made it seem like a good fit.

The more significant issue that I’d like to explore, though, is the problem with pursuing standardization as its own end.

Seeing Like a State

Seeing Like A State - How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed is about one thing: how centrally planned, top-down strategies to improve the world have failed. It covers a lot of centralized standardization efforts, and they all have a lot in common and sound a lot like this ‘unify the queues’ effort.

My favorite example is about trees.

Scientific Forestry

In the 1800s, in Europe, forests were important essential of revenue. A tree could be timber, and a tree could be firewood, and each acre of forest a country owned was valuable. But how valuable?

The problem with forests is that they contain random trees in a random pattern. It’s illegible. You can’t understand at high level what trees you have. You could make a map of it, but it would be hard, and the map would be very complex.

There are many different types of trees, which all might be useful for different things. Reality, it turns out, is a mess.

So the solution was scientific forestry. Let’s make a map of a simplified forest, where it just has the best type of tree spaced out the ideal amount, and we’ll make the whole forest fit that.

(It turns out, by the way, the “best” tree was a Norway spruce. It grows fast and looks like a Christmas tree.)

This went poorly:

The impoverished ecosystem couldn’t support the game animals and medicinal herbs that sustained the surrounding peasant villages, and they suffered an economic collapse. The endless rows of identical trees were a perfect breeding ground for plant diseases and forest fires. And the complex ecological processes that sustained the soil stopped working, so after a generation the Norway spruces grew stunted and malnourished. 1

And you would think that would end things, but managed tree plantations are still popular. And central planning things in a way that looks very uniform on a diagram but doesn’t work well in practice continues today.

James C. Scott calls these top-down solutions legible systems. They are simple to explain at a high level. How does work get processed in that service? The same was as in every other service. What type of tree is that in the forest? It is a Norway spruce, same as all the other trees.

This is the opposite of building a map from the territory.

This is saying let’s take our map and make the territory more like it. 2

The problem from Scott’s perspective is that this push for standardization throws out lots of local, tacit know-how in favor of a system that optimizes for top-down control.

Let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.”

To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

- G. K. Chesterton’s Fence

Standardization ignores Chesterton’s Fence. Why did cities develop to have mixed use zones? Why did this service use a simple database table for queuing? Why do Norway spruce not normally grow here? If you don’t know the answer to these questions then there is a good chance your plan might fail.

This Is Hard

Seeing like a State goes through a lot of examples of this problem. From the book’s perspective grid plan cities, modern zoning, and large-scale architecture projects all repeat the mistakes of scientific forestry. And the mistake is easy to state: it’s trying to make the territory match a map and forgetting that the map ( or architecture diagram ) is just a map. Many local conditions on the ground aren’t reflected in the map.

I don’t mean to say this is a silly mistake that no one should make. It’s easy to make this mistake. If you want to understand how several services handle work in progress, there are many details to absorb. The way we as humans make sense of these things is to abstract over them and group details together. What is common between how all these services do things? You build up an understanding, and then with that understanding, you try to come up with a solution.

What Seeing like a State tells us is that the problem might be trying to come up with a global solution. A global solution, by necessity, has to ignore local conditions. A map has to exclude more things than it includes. A solution that is easier to draw on a whiteboard isn’t necessarily better. It’s just easier to draw.

Going back to the queue example, if Tim had embedded with a team, worked to solve that specific problem, and then embedded with another team and solved another specific problem, then some commonalities may have emerged. Or maybe not. Maybe each situation would need a different solution. Embedding with specific teams, you get to learn the conditions on the ground. Lots of it doesn’t matter, but some of it matters a lot.

The vast majority of knowledge of how the system works is not contained in any book—it’s not contained in some expert’s head—it’s interwoven in heads of all the people who participate in the system.

It’s not just an idea of grand architects for human society… there’s a huge body of local know-how that isn’t really written down anywhere. 3

So now, when I hear about top-down standardization efforts, I get a little worried because I know that trying to generalize across many problems is a fraught endeavor. What’s better is getting to know a specific problem by working collaboratively and embedding with the people who have the most tacit knowledge of the problem. Standardization and top-down edicts fail when they miss or ignore the implicit understandings of people close to the problem.4

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.

Vladpointed out how this idea seems related to Andy Grove’s concept of functional vs mission driven organizations.

↩︎If everything in a company is mission-oriented, then there are no functional departments, meaning that many teams have to reinvent the wheel. If everything in a company is function-oriented, everything gets standardized, but nobody is really happy, because the standard doesn’t fit all needs. Plus in an overly-standardized environment, there is less innovation. It feels like the scientific forest is kinda like a functional-oriented organization.