Getting a Repeatable Build, Every Time

We’re Earthly. We make building software simpler and therefore faster using containerization. Check us out.

EDIT: This post used to be titled How to not use our build tool. It’s a details breakdown of how have a great build process even if you aren’t using Earthly. Thanks to reddit user musman for suggesting the current updated title

Repeatability Matters

In our journey to becoming better software engineers we have learned of various ways in which the team’s productivity could be improved. We noticed that a focus on build repeatability and maintainability goes a long way towards keeping the team focused on what really matters: delivering great software. Many of these ideas helped shape what Earthly is today. In fact, the complexity of the matter is what got us to start Earthly in the first place.

I wanted to sit down and write about all the tricks we learned and that we used every day to help make builds more manageable in the absence of Earthly. It’s kinda like a “what would you do if you couldn’t use Earthly” article. This will hopefully give you some ideas on best practices around build script maintenance, or it might help you decide on whether Earthly is something for you (or if the alternative is preferable).

In this article, we will walk through the 10,000 feet view of your build strategy, then dive into some specific tricks, tools, and techniques you might use to keep your builds effective and reproducible, with other off-the-shelf tools.

Putting Together Complex Builds - Assumptions

Since this is a guide about how not to use Earthly, we’ll try to achieve the same benefits of Earthly, using other tools. Here are some assumptions:

- You are building cloud or web services, targeting Linux.

- You have a setup where multiple programming languages come together (e.g. multiple microservices).

- You would like to have fast local dev-test cycles for individual components.

- You would like to be able to iterate quickly when there is a CI failure.

- Developers on your team use varying platforms for day-to-day development: some Linux, some Mac, some Windows.

- You would like to optimize for cross-team collaboration.

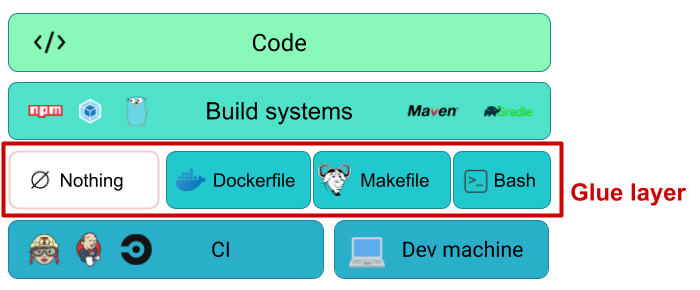

Scope: The Glue Layer

We will focus primarily on the glue layer of your builds. The stuff that brings everything together - maybe it packages things up for releases, or maybe it prepares packages for deployment, or perhaps it is simply a script that the CI definition calls into.

This is a diagram we sometimes use to describe the glue layer. In this article, we’ll be focusing on the Dockerfile, Makefile, and Bash parts of that glue layer. Not having a glue layer can make CI failures difficult to reproduce, or for other teams unfamiliar with the language-specific build tooling to effectively create the right environment to run builds.

The glue layer is the layer between the various projects that need to be built and will act as the common denominator - a vendor-neutral build specification. If we don’t choose such a glue layer, then the CI YAML (or Groovy?) becomes the glue layer and that would mean that it’s more difficult to run it locally for fast iteration.

Because we want to encourage cross-team collaboration, we want to standardize the tooling across teams as much as possible. Different language ecosystems will have different tools and we want to keep using those. You can’t tell the frontend team not to use package.json / npm / Yarn etc - that would be terribly cumbersome for them. So we’re not touching the language-specific build layer.

In addition, because we want to be able to iterate quickly when there are CI failures, we will containerize the build as much as possible. If the failure is part of a containerized script, then it will be easier to reproduce it locally.

A popular choice for the glue layer is to use Makefile + Dockerfile. Makefiles are great as a collection of everyday commands that we can use (make build, make start, make package, make test), while Dockerfiles help keep most of the build containerized.

Another option might be to use bash + Dockerfile, where a collection scripts for everyday tasks exist under a hack or scripts directory (./hack/build, ./hack/test, ./hack/release).

Yet another, more exotic, option is to use another scripting language, such as Python or JavaScript (see, for example, the zx library). Keep in mind, however, that it’s best when most of the engineers can read and write the build scripts with ease. Sometimes too much flexibility of the programming language can make it harder for others to read and understand the scripts. This is an especially important point as the build scripts will likely be read much more often than they will be written.

For this guide, we’ll use Makefile + Dockerfile, as an arbitrary choice. Note, however, that neither Bash nor Makefile is very intuitive at first glance and you will need to help out junior developers, or developers that simply haven’t had the opportunity to learn these yet. And also, these are purely arbitrary choices, based on what we see as popular technologies used in this area. Your own choice may vary for good reasons. This guide is not saying that Makefile / Bash / Dockerfile are the only right choices.

Tips for Taming Makefiles in Large Teams

While there is ShellCheck for linting shell scripts and avoiding the typical pitfalls, there is currently no linter for Makefiles. Part of the reason is that there are multiple styles or philosophies as to how to write Makefiles that it is hard to enforce specific rules that prevent human errors. For example, take a look at this particularly opinionated approach.

Makefiles have the ability to manage the chain of dependencies and avoid duplicate work. However, this feature is heavily based on file creation time (if an input is newer than the output, then rebuild the target), and in most cases that is not enough. If you really want to, it is possible to force everything into that model. However, that tends to create very complicated Makefiles that often only one person on the team understands. This person becomes the “Build Guru” and all build maintenance works flow through them. This “Build Guru” dynamic is very common but best avoided. With Makefiles, using a limited subset of the Makefile language can help avoid this pattern and keep everything more maintainable for the entire team.

If the Makefile wraps an existing build (for example, a Gradle-based or npm-based build), it might make more sense to avoid Makefile’s more advanced features in those particular projects, to help the team be comfortable with making changes to the Makefile, with limited knowledge. In such cases, the caching would be handled by the wrapped build system and not by the Makefile itself.

Here are some guidelines to help keep Makefiles simple and understandable, when the Makefile wraps another build system.

- Only use

.PHONYtargets. Explanation: regular Makefile targets are names of files that need to be output. If the file does not exist or it is older than its inputs,makedecides to run the target. A.PHONYtarget is a target that is not really a file - it’s just a name that the user can use as a short-hand to refer to a recipe to be run..PHONYtargets don’t use the freshness algorithm. - Avoid overusing the distinct features of the different variable flavors (

=vs:=vs?=vs+=vs!=). Someone not knowing the details of how Makefiles work will be confused if the logic relies heavily on the specific flavor. - Avoid order-only prerequisite types (

targets : normal-prerequisites | order-only-prerequisites). Theorder-only-prerequisitecan be misleading to someone new to Makefiles. - Avoid complex rules involving

patsubstor special variables like$<,$^,$*,$@. The way these work is a mystery to Makefile newcomers and it can be really hard to Google for the meaning.

In other words, try not to be too smart about Makefiles. Note, however, that if the Makefile does not wrap an existing build system, then it is likely that you’ll need the advanced features of Makefile to correctly make use of the caching system.

Another thing to consider is that certain UNIX commands vary from platform to platform. For example, sed and find have important differences between GNU/Linux and macOS, and while Windows can behave very much like Linux through WSL 2, testing is needed to verify everything you are using will work the same. Ask a colleague to test out your scripts on their platform if in doubt.

Remember the Tab

Use of the tab character is mandatory in Makefiles or you’ll get this error. This usually catches newbies off-guard.

Makefile:273: *** missing separator. Stop.

Tips for Dockerfiles

To help keep builds reproducible, it’s useful to have a version of the build in containerized form. If performance allows, this might be the day-to-day form that everyone uses. If not, at the very least, it’s the form that is used to debug CI failures.

Dockerfiles are the bread and butter of containerized builds. However, they have an important limitation: they can only output Docker images. They weren’t designed to run unit tests or to output regular artifacts (binaries, jars, packages, etc). However, with some wrapper code, it is possible to extract regular files from images or to execute unit tests too. The following will illustrate how.

Use Multi-stage Dockerfiles or Multiple Dockerfiles

To help split up Dockerfile recipes into logical groupings, you can make use of multiple Dockerfile targets (also called multi-stage builds) and/or of multiple Dockerfile files.

To define targets use FROM ... AS ...

FROM alpine:latest AS my-target-name

...

FROM ubuntu:latest AS another-target-name

...

FROM my-target-name AS yet-another-target-name

...A target can be used in another FROM command or a COPY command (COPY --from=my-target-name <file-from> <file-to>) to copy resulting files from one target into another. This flexibility allows your definition to be more modular, and possibly also more efficient in cache, or more efficient in the size of the final image.

To invoke a specific Dockerfile target, you can use the --target flag of docker build.

docker build --target=my-target-name -t my-build-image .If a target is not specified, docker build will simply build the last target in the file.

Running Containerized Unit Tests

In order to run unit tests in containers, you might take either of the following strategies:

- Run the test as a Dockerfile target

- Build a container with all the necessary code and set the entrypoint to execute the unit tests, then run that container.

A third, less recommended, option is to execute tests as additional layers of the final image. This is not a great option because it unnecessarily bloats your image size and also, there’s no way to skip them. If you just want an image quickly this option will end up getting in your way.

Option a. has the advantage that if nothing changes, the Dockerfile caching will simply reuse previous work and return quickly. Since you don’t need the image being created, you can simply skip mentioning a tag via -t:

docker build .Option b. requires managing an extra image, but might make them look more like the integration tests. Plus, if you want to mount in the source code instead of COPYing it (faster on Linux), this option allows that.

Running Integration Tests

When running containerized integration tests that depend on additional services, only option b. above is available. In such cases, you might want to make use of docker-compose to manage multiple containers running together. Even if your setup is small, it’s just easier to be able to kill everything at once if your tests hang.

Another option is to use testcontainers - a language-specific library that allows you to bring up containerized helper services during integration testing. This can be a great abstraction, however, if you want to keep the integration tests containerized too, you’ll need to mount /var/run/docker.sock (this is sometimes referred to as “docker-out-of-docker”). This will allow the integration test code to bring up the necessary helper services via testcontainers.

docker run -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock ...Either way, to keep your test suite as easy to use as possible, it’s great if you can map the series of commands needed to run the integration tests to a single make command (e.g. make integration) and use this command without any additional settings or wrappers in your CI scripts too. That way, if your CI breaks, then you have a very easy one-liner that should (hopefully) reproduce the failure on your local machine.

Outputting Regular Files

Even the most containerized builds benefit from being able to occasionally output regular files. Here are some possible situations:

- Binaries / Packages / Library archives

- Releasables (deb packages, source code tarballs)

- Screenshots from UI tests

- Test coverage reports

- Performance profile reports

- Database schema init scripts

- Generated source code files (to help IDEs with syntax highlighting)

- Generated configuration

To output regular files as part of a containerized build, there are a few options.

-

Generate the file(s) into a host-mounted volume as part of

docker run. -

Generate the file(s) as part of

docker runand then extract them usingdocker cp. -

Generate the file(s) as the contents of an image during

docker buildthen extract them using thedocker build -ooption. -

Generate the file(s) as the contents of an image during

docker buildthen extract them usingdocker cp.

Let’s take these one at a time:

Option a. Generate the file(s) into a host-mounted volume as part of docker run: This is by far the most used, but arguably the least useful. This technique involves setting the entrypoint as the command that generates the resulting artifact and mounting an output directory (or maybe even the entire source code directory) where the result can be stored and shared with the host system.

docker run --rm -v "$PWD/output:/output" my-image:latest

ls /outputThe typical issue with this approach is that the resulting artifacts are owned by root. Getting rid of them or moving them around then requires sudo. There are, of course, ways to generate the files as a different user within the container, but this can be cumbersome.

Option b. Generate the file(s) as part of docker run and then extract them using docker cp: This option involves executing the docker run and then afterward issuing docker cp to extract the resulting artifact. Here’s an example:

docker run --name build-artifact my-image:latest

docker cp build-artifact:/output/my-artifact ./output/my-artifact

docker rm build-artifactThis option will produce results owned by the right user. The one possible downside of this approach is that if the docker run fails, a hanging build-artifact container remains, which will cause the next run to fail due to naming conflict. This can be easily fixed, however, by adding docker rm -f build-artifact at the beginning of the script.

Option c. Generate the file(s) as the contents of an image during docker build then extract them using the docker build -o option: This is a lesser-known technique particularly suited for outputting entire directories. It essentially outputs the root directory of an entire image to the host. Here’s how this might be used.

FROM alpine AS base

RUN mkdir -p /output

RUN echo "contents" >/output/my-artifact

FROM scratch

COPY --from=base /output/* /docker build -o ./output .

cat ./output/my-artifact # prints "contents"The use of the scratch base image is such that the final image is minimal and only the required artifact is copied over to the host.

This technique outputs files owned by the right user, however sometimes the fact that it outputs a whole directory can be limiting.

Option d. Generate the file(s) as the contents of an image during docker build then extract them using docker cp: This technique is somewhat similar to option b. except that no docker run is used.

docker build -t my-image:latest .

docker create --name output-artifact my-image:latest

docker cp output-artifact:/output/my-artifact ./output/my-artifact

docker rm output-artifactThis option too will produce artifacts owned by the right user.

Tips for Taming Bash Scripts

Regardless of the build setup, bash scripts are sometimes inevitable, especially when extensive release logic is needed and the language-specific tooling doesn’t offer specific support.

If you’re new to bash scripting, I’ll run through a few of the more useful beginner tricks from our understanding bash article.

- Spaces are surprisingly important.

A=Bis different fromA = B. Alsoif[$A=$B]does not work - it has to beif [ $A = $B ]. - Variables can cause really weird things if they are not wrapped in double-quotes. The reason is that a variable that contains spaces can expand across multiple command parameters unless it’s within quotes. To prevent any surprises, a good rule is to never expand a variable outside of double-quotes. So use

"$ABC"always and not simply$ABC. - A really good tool to check for some common errors like the above is

shellcheck. - If there is an error in a bash script, by default, the script simply continues without a worry. This is very often not what you want - you want to terminate immediately so that the user is aware that something has failed. To enable this, put

set -eat the top of the file. - A series of piped commands can also fail and bash doesn’t terminate by default. To terminate immediately in such cases, you can enable

set -o pipefail. - An undefined variable is treated as the empty string in bash. However a lot of times an undefined variable can also be caused by a typo, or an incomplete rename during a refactor, or some other human error. To avoid surprises, you can do

set -u, which will cause the script to fail on undefined variables. To initialize a variable with a default value (and avoid this error, if you’d like to allow an optional external variable), you can use: "${<variable-name>:=<default-value>}". Just don’t forget the:in front of it. - If you have no idea what your bash script is doing, you can make it print every statement being evaluated using

set -x. It’s especially useful when debugging.

Importing Code and Artifacts from Another Repository

Sometimes it’s useful to import the result of one build from repo A into the build of repo B. Here are some examples of situations where this is needed:

- Building some binaries in a core repo and packaging the release in a “build-tooling” repo (example in Kong)

- Generating protobuf files in one repo and reusing those files in multiple other repos (client(s) and server)

- Pre-computing some initialization data in one repo and using it in another repo

- Cases where the language-specific tooling offers little or no support for importing code from another repository

There are multiple ways to achieve importing on your own. In general, if the language you use provides solid importing mechanisms, there is little to no reason to build any scripting that does the same thing. In other cases, you might go with one of the following makeshift options:

- Git clone

- Submodule

- Pass files via a Docker image

- Pass files via S3

Option a. Git clone: This relies on git-cloning one repo from within the other. It’s especially useful when the code itself is needed and not necessarily an artifact resulting from building that code. Here how this might be achieved in a Makefile:

my-dep: ./deps/my-dep

./deps/my-dep:

mkdir -p deps

rm -rf ./deps/my-dep

git clone --branch v1.2.3 <clone-url> ./deps/my-dep

clean:

rm -rf ./depsAlthough it’s relatively crude in that it wipes the whole dir and re-clones it when necessary, it’s also pretty robust because there’s nothing assumed about the state of that directory. (Just make sure you’re not making important changes in that directory as those may be lost!)

The --branch setting takes any git tag, sha, or branch, or, in general, a git ref. This helps pin the dependency to something specific if that is needed.

You’ll need to be careful about how you use the <clone-url> as some engineers will use HTTPS auth, while others will use ssh auth. You might want to standardize on only one of the two options and use git’s insteadof feature if an individual developer would like to switch to the other URL.

For example, if a developer wants to dynamically switch from https:// to SSH GitHub URLs, they can do:

git config --global url."git@github.com:".insteadOf "https://github.com/"Option b. Submodule: This is another popular option especially when the source code itself is also needed. The technique involves relying on the git submodule capabilities built into git.

The way it works is that git marks certain paths within the repository where submodules (other git repositories) can be cloned into. You can use the following command to add such submodules:

git submodule add <clone-url> <path>This command clones the referenced repository into that path and also adds a .gitmodules file in the root of your repository, which might look like this.

[submodule "<name>"]

path = <path>

url = <clone-url>Besides this entry, git internally also stores the git sha of the submoduled repository, so it is tied strongly to a specific version of it.

Although there is significant tooling out there for working with submodules, some people don’t enjoy them because they require adjusting the typical git workflow to account for maintaining the submodules. In some cases, when submodules are overused, they can create more confusion than necessary. You can tell things can get complex when git comes with commands like git submodule foreach 'git stash'.

There is much more to submodules than is in scope for this guide, but a good run-down can be found in the git official documentation.

Option c. Pass files via a Docker image: This option involves creating a Docker image that is not really actually run. It is merely used as a package repository.

The advantage of this technique is that Docker images support tags, which allow for embedding into a release-process-based workflow. This technique is especially useful when artifacts beyond the source code itself are needed. Things like binaries, or generated files.

However, this option does require repo A to execute a build that packages up the image before it can be used in repo B. If options a. and b. are simply commit to repo A -> use in repo B, for option c. the sequence is commit to repo A -> wait for CI build of repo A to complete -> use in repo B.

Side Note. If the CI is slow, this can be a productivity hog. To counter this situation, make sure that the individual engineer on the team can build the image independently from the CI, in order to be able to iterate locally quickly.

Here’s how this option works in general.

Repo A:

FROM scratch

COPY ./build/files ./docker build -t my-registry/my-artifacts:my_tag .

docker push my-registry/my-artifacts:my_tagRepo B:

docker pull my-registry/my-artifacts:my_tag

docker create --name output-artifacts my-registry/my-artifacts:my_tag

docker cp output-artifacts:files ./deps/files

docker rm output-artifactsThe nice thing about this approach is that Docker will use its cache if an artifact has not changed.

Option d. Pass files via S3: This option is very similar to option c., except that it uses an S3 bucket instead of a Docker registry for storing artifacts.

Although I’ve heard this being used as a viable alternative, I’ve never seen this in action myself. With the wide range of Docker registries available out there, I don’t think this option is necessarily better. If, however, your company for whatever reason cannot provide you with a Docker registry repository, just know that using S3 (or any other cloud blob store) is also a possibility.

Parallelism With Makefiles and Dockerfiles

The bread and butter of improving build speed are caching and parallelism. We will look at each of these topics in the context of Makefiles and Dockerfiles.

Makefiles have parallelism support out of the box. Running any make target with the -j option tells Make to execute dependencies in parallel (e.g. make -j build). Although this is a seemingly easy win for performance, it comes with a number of strings attached, that you should be aware of.

First of all, Make targets are not isolated - they all operate on the same directory. When you run multiple such targets in parallel, you may get very surprising results due to race conditions. Imagine if, for one of your targets, you really want to run a clean build, so you make it depend on the target clean. And then you have another target, which ensures that your build directory has been created. Well if these run in parallel, you can imagine how they could get in each other’s way.

To really make use of this option, you’ll need to design target dependencies with parallelism mindfulness. You’ll need to really think about dependencies whether they need to be built in a certain order, or if they can be built in any order.

If you need dependencies to be built in a specific order, a great way to achieve that is to use recursive Make calls:

build:

$(MAKE) dep1

$(MAKE) dep2

$(MAKE) dep3

actually buildIf dependencies can execute in any order, then declaring them as regular target dependencies will be fine:

build: dep1 dep2 dep3

actually buildNote that these principles may be difficult to uphold in a large team, as not all engineers will be running the build with the parallel option turned on. So a lot of times the parallelism capability is not tested, and as a result, it can break often. Keep these things in mind as you may need to reinforce the use of parallelism in project READMEs to hopefully be better supported by individual PRs.

Another, either alternative or complementary option, is to make use of Dockerfile parallelism. With BuildKit turned on (DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build ...), Dockerfiles are built with parallelism automatically, if they involve multiple targets. So for example, if you have targets dep1, dep2 and dep3 and you COPY files from them like so:

FROM alpine AS build

COPY --from=dep1 /output/artifact1 ./

COPY --from=dep2 /output/artifact2 ./

COPY --from=dep3 /output/artifact3 ./

RUN actually buildThen dep1, dep2, and dep3 will be executed in parallel. The nice thing about this is that there is nothing shared between these three targets (unlike the Makefile case) and they will just work in parallel. No special considerations are necessary.

Shared Caching

Another way to speed up builds is to make use of shared caching. Shared caching is especially relevant in modern CI setups where the CI task is sandboxed. Because the CI is sandboxed, it cannot reuse the result of a previous build.

There are, of course, CI-supported cache saving features. However, those features are not usable when testing locally. And in the end, all that CI caching does is just upload a file or directory to cloud storage, which can be downloaded later in another instance of the build.

Dockerfile builds have pretty powerful cache saving and importing capabilities, thanks to the new BuildKit engine. To use these capabilities, you need to first enable BuildKit (DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build ...) and then pass the right arguments to turn these features on.

First, you need to push images together with the cache manifest:

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build -t my-registry/my-image --build-arg BUILDKIT_INLINE_CACHE=1 .

docker push my-registry/my-imageAnd then you need to make use of the cache in subsequent builds using --cache-from:

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build --cache-from=my-registry/my-image -t my-registry/my-image .Doing both in the same command looks like this:

DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build --cache-from=my-registry/my-image -t my-registry/my-image --build-arg BUILDKIT_INLINE_CACHE=1 .

docker push my-registry/my-imageIf the image does not already exist (or if it does not have a cache manifest embedded), there will be a warning, but the build will work fine otherwise.

Managing Secrets

Mature CI/CD setups often hold more secrets than there are available in the production environment. That’s because they often need access to registries, artifact repositories, git repositories, as well as staging environments where additional testing can be performed, and also the production environment itself, where live releases are deployed to, together with schema write access to DBs for upgrades, and also possibly S3 access. Wow - that’s a mouthful.

Oh, did I also mention that the CI runs a ton of code imported from the web? That npm install one of your colleagues ran in CI will download half the internet. And not all of it is particularly trust-worthy.

This whole thing makes for an incredibly risky attack surface. Giving access to build secrets to every developer adds an unnecessary extra dimension to the whole risk.

However, to be able to reproduce some of the builds, you really need to give at least some access. At the very least, developers need read access to most Docker registries and artifact repositories / package repositories. In fact, if you want to ensure that artifacts and images that make it to production are never created on a developer’s computer (because you don’t know if their specific environment will produce the releasable correctly consistently), you can simply not give out write access to any Docker repository and make it a rule that only the CI may have write access. (You might still need separate, non-production repos for local testing, though).

For the read access, it’s best if each engineer gets their own account and credentials. In case someone is terminated, you can simply revoke access from that engineer’s account and know that all other credentials are not compromised.

For reproducing CI/CD failures in pipelines with more sensitive access, you will need to maintain a small list of employees who will receive more privileged production access.

To share the initial credentials with each engineer, if an email invite feature is not provided by the system, it’s best to use a password manager to send credentials one-to-one. Sometimes this process gets fairly manual in larger teams, but for the reasons mentioned above, it’s important to maintain segregated access.

For a seamless setup, you can also store build credentials in HashiCorp Vault and use the Vault CLI in scripts to read secrets where they are needed.

vault read -field=foo secret/my-secretThis may be helpful in setups where extensive use of build credentials is required. Managing a Vault installation, however, is a whole project of its own, and going into those details is perhaps a story for another day.

Maintaining Consistency

Now to turn to a more philosophical aspect of builds. A great build setup is one where every engineer can understand what it does fairly quickly and where every engineer can contribute with minimal to no help at all. Although these principles are obvious goals to have, the norm is quite the opposite.

Engineers don’t have an innate need to mess things up. It’s not like we wake up in the morning trying to make builds cumbersome and complex for everyone else. The issue is usually that builds simply grow organically into an eventual big hairball of mess.

The result of this is that new team members have difficulty making sense of the build scripts and colleagues from other teams have difficulty in contributing to your team’s project, thus creating integration gaps.

Think about how this is in your organization. Is it difficult for you to contribute to another team’s codebase? Do you know how to run the project’s unit and integration test suites? Is there even an integration test between the two projects?

To help teams meld with each other, it’s particularly important to have a standard way to build and test any project in the organization. If the build is containerized and everyone has read access to the right base images, then everyone can build and test each other’s codebases, thus eliminating at least one of the natural barriers that get formed between engineering teams.

If you want to go a step further, you can even standardize a set of commands for the repositories across the organization. For example:

make build- builds the projectmake test- runs the unit testsmake integration- runs the integration testsmake ci- executes the same script that is run in CI

Then your engineers will be able to build another team’s codebase in their sleep!

Other Options

This article wouldn’t be complete without mentioning that if you’re a large organization (thousands of engineers), you can also take a look at some large-scale build systems as popular alternatives to in-house scripts. The names that come to mind are Bazel, Buck and Pants. These systems imply heavy organization buy-in and well-staffed build engineering teams to manage them.

Some of these can provide some of the most advanced capabilities available on planet Earth, however, they do come with the tradeoff that they don’t integrate well with most open-source tooling and so all projects need to be adapted to fit the paradigm.

If you’d like to get started exploring these, we have previously written about Monorepos and Bazel.

Parting Words and Mandatory Plug

Getting everyone to write containerized builds is difficult in a growing organization. As you can see from this article, certain operations within containerized builds are not trivial to achieve and the wheel may be reinvented many times across the different teams.

For these reasons, we have built Earthly. Through Earthly, we wanted to give containerized builds to the world, for the sake of reproducibility. From our own experience, we saw that Dockerfiles alone are not meant as build scripts, but rather as container image definitions. In true Unix philosophy, they are a great tool for that specific job - they do one thing and they do it well. To go the extra step and have containerized builds scripts (not just image definitions), a number of tricks and wrappers are necessary. Earthly takes the best ideas from Dockerfiles and Makefiles and puts them into a unified syntax that anyone can understand at-a-glance.

Give Earthly a try and tell us what you think via our Slack or our GitHub issue tracker.

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.