How Classes and Objects Work in Python

We’re Earthly. We streamline software building using containerization. If you’re working with Python, Earthly can simplify your build process. Check it out.

If you’re a developer looking to level up your Python skills, adding OOP to your Python box can be helpful. This tutorial will help you get started with object-oriented programming in Python.

Python is one of the most-loved programming languages that supports procedural, functional, and object-oriented programming paradigms.

Procedural programming works fine for simple and smaller projects. But as you start working on larger applications, it’s important to organize code better. Object-oriented programming lets you group related data and functions logically. It also facilitates code reuse and lets you add functionality on top of existing code.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to:

- Create and work with classes and objects in Python

- Define instance attributes and methods

- Define class variables and methods

- Use class methods as constructors

- Define static methods

How to Create Classes and Objects in Python

Python natively supports object-oriented programming and all variables that you create are objects. You can start a Python REPL and run the following line of code: it calls the type() function with py_num as the argument. The output reads <class 'int'> which means py_num is an object of the integer class.

>>> py_num = 8

>>> type(py_num)

<class 'int'>You can verify this for a few more built-in data types.

>>> py_str = "A Python String"

>>> type(py_str)

<class 'str'>

>>> py_list = [2,4,9]

>>> type(py_list)

<class 'list'>Like all modern programming languages, Python lets you create custom classes. A class is a template or a blueprint from which you can create objects of the class, also called instances.

To create a class, you can use the class keyword followed by the name of the class: class ClassName. By convention, the class names are specified in Pascal case—where the first letter of each word in a variable name is capitalized.

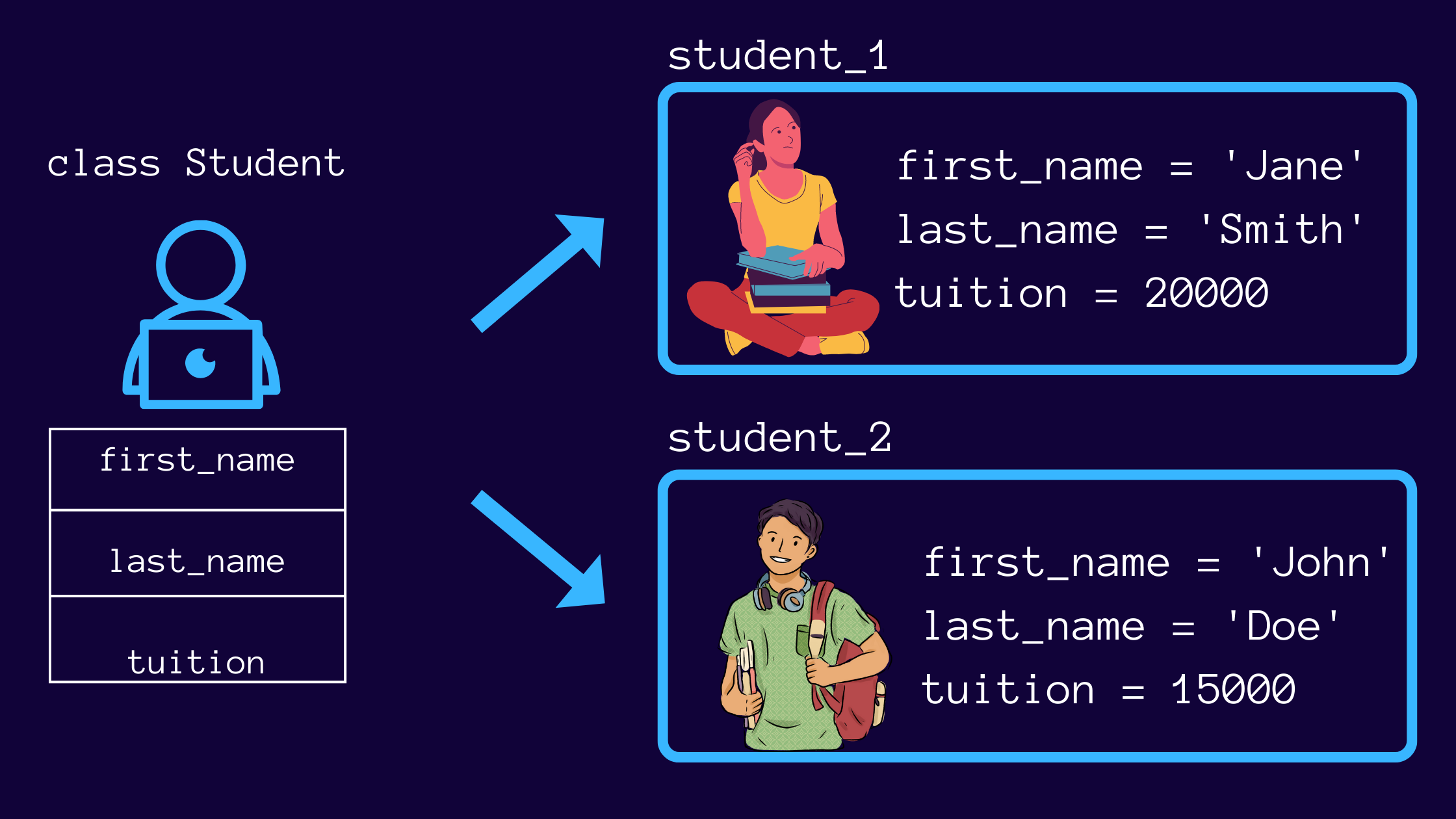

In this tutorial, let’s consider the example of Student class—containing student records for a given academic year.

You may download the code and follow along.

All of the code below is in the main.py file.

class Student:

pass # placeholder for code that we'll write shortly!After you’ve created a class, you can create an object by calling the class as if it were a function.

student_1 = Student()To verify if the created object is an instance of a particular class, you can use one of the following methods:

Call the

type()function with the object name as the argument.Call the

isinstance()function.isinstance(<object_name>,<ClassName>)returnsTrueif<object_name>is an instance of the class<ClassName>; else it returnsFalse.

print(type(student_1))

print(isinstance(student_1,Student))# Output

<class '__main__.Student'>

TrueUnderstanding Instance Attributes and Methods

The data associated with the objects or instances are called attributes. The actions that the objects can perform or allow us to perform on them are called methods.

After you’ve created an instance, you may define attributes using <object_name>.<attribute_name> = <value>.

However, this doesn’t facilitate code reuse and there’s no advantage of using a class. You’ll want to programmatically initialize these attributes with their respective values—whenever you instantiate an object. To do this, you can use the __init__ method which serves as the class constructor.

How the __init__ Method Works

The __init__ method is the class constructor that helps initialize the attributes of instances. All methods defined inside the class are indented by four spaces.

Whenever a method is defined inside a class, it takes the instance of the class as the first argument and is usually named self.

The usage of self as the first parameter is a recommended practice according to the PEP 8 Style Guide and is not a strict requirement.

class Student:

def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,tuition):

self.first_name = first_name

self.last_name = last_name

self.tuition = tuitionWhenever you create an instance of the class Student, the __init__ method does the following:

- It automatically takes in the instance as the first argument (denoted by

self). In this example, instance denotes a particular student object. - It assigns the values of the parameters,

first_name,last_name, andtuitionto the instance attributesfirst_name,last_name, andtuitionof the specific instance.

To improve readability, you can consider giving the same names to both the attributes and the parameters in the __init__ constructor, but different names, as shown in the code snippet below, would work just fine.

class Student:

def __init__(self,fname,lname,tuition_amt):

self.first_name = fname

self.last_name = lname

self.tuition = tuition_amtSumming up what we’ve learned so far: The Student class serves as a template—with attributes first_name, last_name, and tuition—from which we can create student objects each having their own first and last names, and an associated tuition.

As the above attributes are unique to a specific object, they are referred to as instance attributes or instance variables.

Now that you’ve defined the __init__ method, you can instantiate objects with the desired values for instance attributes, as shown below.

student_1 = Student('Jane','Smith',20000)

student_2 = Student('John','Doe',15000)How to Define and Call Instance Methods

In addition to the __init__ method, you can define other methods that act on the instances of the class, often accessing and modifying the instance attributes. Such methods are rightly named instance methods.

Let’s revisit the Student class example.

Given the attributes first_name and last_name, we can define methods that use these attributes and return the full name and email for each student object. We name these methods get_full_name() and get_email(), respectively . Remember, all instance methods take the instance (self) as the first argument.

class Student:

def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,tuition):

self.first_name = first_name

self.last_name = last_name

self.tuition = tuition

def get_full_name(self):

return f"{self.first_name} {self.last_name}"

def get_email(self):

return f"{self.first_name}.{self.last_name}@school.edu"To call an instance method you can use, <instance_name>.<method()>. You can also call an instance method using the class with the syntax: <ClassName>.<method>(<instance_name>). Though verbose, this method helps understand how the instance is passed in as the first argument.

# calling instance method on the instance

print(student_1.get_email())

# calling instance method using the class

print(Student.get_email(student_2))# Output

Jane.Smith@school.edu

John.Doe@school.eduWhat Are Class Variables and How to Use Them?

So far, you’ve learned how to define instance variables, specific to an instance or object of the class, and instance methods that operate on the instance variables.

However, there are times when you’ll need certain attributes that remain the same for all instances of a particular class. You can define such attributes as class variables.

Typically, class variables are defined before other instance and class methods that’ll use them.

Initializing and Accessing Class Variables

For example, in the Student class, if you’re maintaining the student records for a given academic year, then there can be a class variable, academic_year that will remain the same for all student objects created from the Student class.

We can define another class variable, num_students that keeps track of the number of student objects created. Every time you create a new student object, the value of num_students is incremented by 1.

class Student:

academic_yr = '2022-23'

num_students = 0

def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,tuition):

self.first_name = first_name

self.last_name = last_name

self.tuition = tuition

Student.num_students +=1

def get_full_name(self):

return f"{self.first_name} {self.last_name}"

def get_email(self):

return f"{self.first_name}.{self.last_name}@school.edu"You can access class variables using the syntax: ClassName.var_name.

student_1 = Student('Jane','Smith',20000)

student_2 = Student('John','Doe',15000)

print(Student.academic_yr)

print(Student.num_students)We’ve created two student objects, hence the value of the class variable num_students is now 2.

# Output

2022-23

2How to Use Class Methods in Python

In addition to class variables, you can also define class methods that bind to a class. Such methods do not access any of the instance attributes but can be used to set the value of a class variable or function as an alternative class constructor.

Suppose the university sets the value of fee_waiver, a number between zero and one—indicating the fraction of the tuition to be waived. Instead of hardcoding it as a class variable, you can define a method that sets the value of fee_waiver.

To convert an instance method to a class method, you can use the @classmethod decorator in Python. By convention, the first argument in class methods is cls, just the way the first argument in instance methods is self.

@classmethod

def set_fee_waiver(cls,fee_waiver):

cls.fee_waiver = fee_waiverNow that you’ve defined the class method, you can define an instance method apply_fee_waiver() that applies the fee waiver and returns the updated tuition for any student object.

def apply_fee_waiver(self):

self.tuition -= self.tuition*Student.fee_waiver

return self.tuitionLet’s set the fee_waiver and apply the fee waiver for student_1.

Student.set_fee_waiver(0.1)

print(student_1.apply_fee_waiver())# Output

# 0.1*tuition has been waived

18000.0Decorators in Python: An Overview

Let’s start with an example.

def add(x,y):

return x + yHere, add() is a function that takes two numbers and returns their sum.

Say, we would like to modify this function by doubling each of the arguments before addition. We could change the return statement to read: return 2*x + 2*y but what if you no longer wanted to double the arguments? In that case, you’ll have to modify the function definition yet again. Enter decorators.

In Python, a decorator is a function that extends the functionality of existing functions without modifying them explicitly. As explained earlier, all variables in Python are inherently objects, so are functions. Therefore, you can pass in functions as arguments to another function and you can define a function that returns another function.

Read through the code snippet below.

def double_xy(f):

def wrapper(x,y):

return f(2*x,2*y)

return wrapperLet’s parse the definition of double_xy().

- The function

double_xy()accepts a functionfas the argument. - In the body of the function, we define a

wrapper()function that is parameterized byxandy. - The

wrapper()returns the functionf, called with2*xand2*yas the arguments. - The function

double_xy()returns the innerwrapper()function.

Next, you can call the function double_xy() with add as the argument and assign it (again) to add—just the way you’d call a function and assign its return value to a variable.

When you now call add() with values for x and y, it returns the sum of 2*x and 2*y.

add = double_xy(add)

add(1,2) #6 Instead of the above verbose syntax, you have a succinct syntax. Just add @double_xy above the definition of the add() function, as shown below.

@double_xy

def add(x,y):

return x + y

add(1,2) #6Therefore, the function double_xy() decorates the add() function to have the property of doubling the arguments and computing their sum.

At this point, we have the following code in the main.py file.

class Student:

#class variables

academic_yr = '2022-23'

num_students = 0

def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,tuition):

self.first_name = first_name

self.last_name = last_name

self.tuition = tuition

Student.num_students +=1

def get_full_name(self):

return f"{self.first_name} {self.last_name}"

def get_email(self):

return f"{self.first_name}.{self.last_name}@school.edu"

@classmethod

def set_fee_waiver(cls,fee_waiver):

cls.fee_waiver = fee_waiver

def apply_fee_waiver(self):

self.tuition -= self.tuition*Student.fee_waiver

return self.tuition Next, let’s proceed to learn how to define class methods that can be used as constructors.

How to Use Class Methods as Constructors

Suppose instead that the student data are available in the form of tuples - one tuple for each student. In this case, you should unpack the tuple into three variables, and then proceed to instantiate the object.

student_tuple = ('Jane','Smith',20000)

first_name,last_name,tuition = ('Jane','Smith',20000)

student_1 = Student(first_name,last_name,tuition)When you need to instantiate many objects, you’ll have to repeat the unpacking step for each of the tuples—which is repetitive and suboptimal.

You can define a class method from_tuple() that unpacks the tuple and assigns the values to the attribute names. You can then return a reference to the class, which allows us to instantiate objects by calling the class method.

@classmethod

def from_tuple(cls,student_tuple):

first_name, last_name, tuition = student_tuple

return cls(first_name,last_name,tuition)Now, you can create student objects from the tuples using the from_tuple() method as the constructor.

student_tuple_1 = ('Jane','Smith',20000)

student_1 = Student.from_tuple(student_tuple_1)

student_tuple_2 = ('John','Doe',25000)

student_2 = Student.from_tuple(student_tuple_2)You can define variants of the above class constructors to construct objects by parsing Python strings, JSON files, and more.

How to Use Static Methods in Python

Suppose you’d like to define a method that is related to the class; but you don’t need to access any of the class and instance variables inside it. In this case, you should consider defining it as a static method.

For example, in the Student class, you can define a method is_fall() that takes in a date and checks whether or not the ongoing semester is the fall semester.

To work with dates, let’s import the date class from Python’s built-in datetime module.

from datetime import dateTo define a static method, you can use the @staticmethod decorator. Assuming that the months September, October, and November correspond to fall, we check if the month attribute of the date—passed in as the argument to is_fall()—is in the list [9,10,11].

Let’s add the following definition of is_fall() to the class.

@staticmethod

def is_fall(date):

if date.month in [9,10,11]:

print("Yes, the fall semester is in progress.")

else:

print("Not the fall semester")Even though a static method is not bound to the class or an instance of the class, it’s still present in the namespace of the Student class. You can call the static method just the way you’d call any class method in scope with the syntax: ClassName.static_method(). Let’s call is_fall() with today’s date as the argument, and it’s not fall yet in 2022.

today = date.today()

Student.is_fall(today)# Output:

Not the fall semesterPutting it all together, we have the following code in the main.py file.

from datetime import date

class Student:

academic_yr = '2022-23'

num_students = 0

def __init__(self,first_name,last_name,tuition):

self.first_name = first_name

self.last_name = last_name

self.tuition = tuition

Student.num_students +=1

def get_full_name(self):

return f"{self.first_name} {self.last_name}"

def get_email(self):

return f"{self.first_name}.{self.last_name}@school.edu"

@classmethod

def set_fee_waiver(cls,fee_waiver):

cls.fee_waiver = fee_waiver

def apply_fee_waiver(self):

self.tuition -= self.tuition*Student.fee_waiver

return self.tuition

# class method as constructor

@classmethod

def from_tuple(cls,student_tuple):

first_name, last_name, tuition = student_tuple

return cls(first_name,last_name,tuition)

@staticmethod

def is_fall(date):

if date.month in [9,10,11]:

print("Yes, the fall semester is in progress.")

else:

print("Not the fall semester")Conclusion

In this tutorial, we explored Python’s classes and objects, using classes as templates to make objects with instance attributes and methods. We learned about class variables and methods, which share values across all instances and serve as alternate constructors, respectively. We also discussed static methods not tied to a class or instance.

As we continue to level up our Python skills, it’s also worth considering how we can optimize our build automation. If you’re interested in this, you might want to check out Earthly.

Next up, we’ll learn about extending class functionality with Python inheritance. Stay tuned!

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.