Guide to Kubernetes Networking

We’re Earthly. We simplify and speed up software builds using containerization. If you’re working with Kubernetes networking, Earthly can be a handy sidekick, making your containerized builds a breeze. Give us a look.

Kubernetes networking enables the components that make up the Kubernetes ecosystem, like containers, pods, and services, to communicate effectively with each other. As a result, networking permeates Kubernetes.

Because Kubernetes is primarily a distributed system, it relies on networks to operate effectively. Therefore, a guide discussing Kubernetes networking is an invaluable resource to anyone interested in Kubernetes. Whether you simply want to understand how Kubernetes excels at container orchestration or implement service discovery, networking will impact your work.

In this guide, you’ll learn about the Kubernetes network model as a whole and how external clusters can communicate.

Why Kubernetes Networking Is Important

Understanding how Kubernetes networking works is central to grasping how the components of your application will communicate and exchange information. The most significant of these is the communication between containers and the communication between pods. Others include communications from a pod to a service and external, source-to-service communication.

Kubernetes also provides various types of container networking solutions. Therefore, you need to have a firm grasp of Kubernetes networking to understand which type of solution best meets your needs.

Overview of the Kubernetes Network Model

Kubernetes is designed to run and manage distributed systems of cluster machines. Because of this, it’s necessary to simplify the cluster networking process as much as possible. Part of the intent to simplify Kubernetes networking is the decision to base the platform on a flat network structure.

A flat network topology is ideal for Kubernetes for a variety of reasons. It’s easy to implement, and it reduces complexity because all devices are connected to a single switch. The structure also lacks segmentation or hierarchical layers, so traffic doesn’t need to go through intermediaries, like routers.

The most salient feature of a flat network structure is that you don’t need to map the host’s port to container ports. But why is this compelling? Well, because of the port allocation problem it creates.

Pods and the Problem of Port Allocation

In a host network mode, a container uses the IP address and network namespace of its host node. For this reason, a container needs a port from its host in order to expose its application.

An application might be deployed across several containers, which requires several ports to run. In addition, a port on the host machine is bound to the application port on a container. With a large deployment of containers requiring numerous ports, you’ll soon encounter the problem of port allocation.

This means you’ll need to keep track of all ports that are allocated on the host, or you risk running into conflicts. This is a Herculean task, given that there are 65,535 ports available on a typical computer and would possibly require applications to pre-declare their ports.

The IP-per-pod approach was Kubernetes’s solution to the port allocation problem. In this approach, pods are conceived as a more efficient solution because they remove the need to maintain ports. Instead of deriving its ports from the host machine, the container now gets its ports from its pod’s namespace.

Kubernetes Network Requirements and Conditions

The pod IP and its associated network namespace are subsequently shared by all the containers running inside the pod. The pod IP also connects its containers to other pods running in the cluster.

Following are the fundamental networking concepts on which the pod abstraction is based:

- All containers within a pod share the same network namespace.

- All containers in a pod can communicate with each other through the localhost since they share the same namespace.

- Every pod is allocated a unique IP address and port range.

- A pod’s IP address is reachable from all other pods existing in the Kubernetes cluster without requiring any Network Address Translation (NAT).

Network administrators need to follow certain guidelines to achieve a flat network structure imposed by Kubernetes. These guidelines are as follows:

- Pods (and containers) can communicate with each other without requiring any NAT.

- Nodes can communicate with all pods/containers without needing any NAT.

- The IP address that the container (or pod) sees is the same as what others see.

IP Allocation in Kubernetes Components

Kubernetes utilizes various IP ranges to facilitate Kubernetes networking. These IP ranges determine how IP addresses are assigned to nodes, pods, and services.

Defining these IP ranges is useful, especially when your Kubernetes setup has to deal with external systems, like firewalls, that make decisions based on the ranges. Every node is a virtual or physical host machine whose IP address is derived from its cluster’s VPC network.

In the case of pods, Kubernetes uses Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) to assign the pool of IP address ranges. Therefore, each pod emerges with an IP address allocated from the pod CIDR range of its host node.

To achieve IP allocation in Kubernetes, it’s also necessary to understand IP address management (IPAM) functions. IPAM is used for allocating and managing IP addresses used by IP endpoints.

Most Kubernetes deployments use an IPAM plug-in to perform the task of allocating and managing their pod IPs. IPAM plug-ins provide network admins with different sets of features to choose from. This is particularly true when using a plug-in known as a container network interface (CNI) (more on this later).

Kubernetes Networking Implementation

A major reason for Kubernetes’s popularity is the flexibility it affords network administrators to configure their network. This is manifested in the diversity of options it provides for IPAM implementation.

Although the pod is the main abstraction in Kubernetes, the framework is still centered on container orchestration. As a result, part of Kubernetes’s flexibility comes from API plug-ins, also known as CNIs.

Container Network Interface API

A CNI is a framework for configuring network resources dynamically. It’s typically designed as a plug-in-oriented network solution specifically for containers. A CNI consists of specifications derived from the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) project and libraries. These libraries show how to write plug-ins to configure network interfaces in containers.

So a CNI connects containers across nodes. In practical terms, a CNI acts as an interface between a network namespace and a network provider, which could be another network plug-in or a Kubernetes network.

A CNI plug-in gives you more control over your network resources by providing you with a framework to manage and configure them dynamically.

Here are some common third-party CNI plug-ins for Kubernetes:

- Project Calico is an open-source, Layer 3 VPN (L3VPN) with security policies that can be enforced on your service mesh layers and host networking. It also provides a scalable network solution for Kubernetes.

- Flannel is an overlay network suited for Kubernetes requirements and uses etcd to store its configuration data.

- Weave Net, unlike the others, is a proprietary, simple tool with one IP address per pod and ideally suited for Kubernetes.

Services and Their Implications for Kubernetes Networking

Pods are the smallest deployable unit in Kubernetes and are routinely created and destroyed to manage the state of the cluster. Therefore, the IP address assigned to a pod is ephemeral.

Due to the unstable nature of pods, clients cannot reliably depend on their IP addresses for endpoint connectivity. Services were conceived to resolve this problem.

A Service is an abstraction designed to provide stable network access to a logical set of pods. There are five types of Services in Kubernetes, and they handle different types of communications. They include the following:

- NodePort exposes pods to external traffic through an open, static port on the worker node.

- ClusterIP (default) assigns a virtual IP, known as the ClusterIP, for internal communications within the Kubernetes cluster.

- LoadBalancer provisions an external load balancer to expose the Service.

- ExternalName only uses DNS names because it doesn’t have selectors.

- Headless is a Service that doesn’t have or require an IP address.

Frontend clients only need to know the ClusterIP. This allows the Service to provide a network abstraction that lets the pods associated with the Service change at any time. This effectively decouples a Service from its underlying pods.

For example, take a look at the Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE) Guide. As you can see in the following code, you can use this manifest to create a Service deployment with three pod replicas in your my-deployment.yaml file:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: my-dev-deployment

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: metrics

department: sales

replicas: 3

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: metrics

department: sales

spec:

containers:

- name: hello

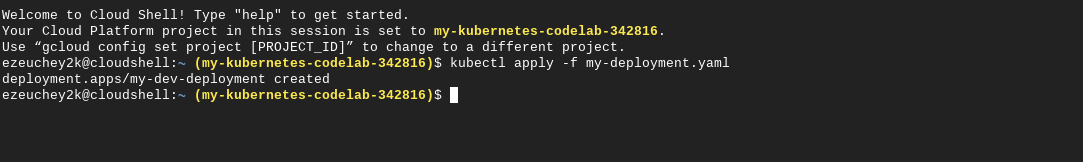

image: "us-docker.pkg.dev/google-samples/containers/gke/hello-app:2.0"kubectl apply -f [YAML/MANIFEST_FILE] to create the deployment. The output will look like this:

kubectl get pods:

After the pods are created, it’s time to create a Service to expose them. The ClusterIP is a virtual IP that serves as a proxy to pods and load balances their requests. Selectors and their associated labels are used to determine the pods targeted by a Service.

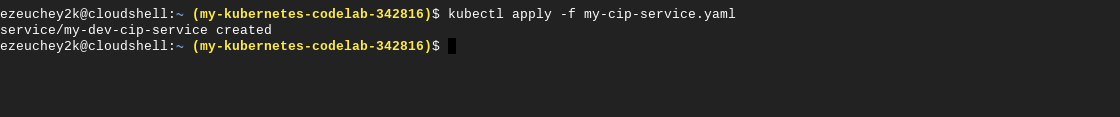

To create this Service, simply run kubectl apply -f [YAML/MANIFEST_FILE].

The YAML for a ClusterIP Service looks like this:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: my-dev-cip-service

spec:

type: ClusterIP

# Uncomment the below line to create a Headless Service

# clusterIP: None

selector:

app: metrics

department: sales

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

targetPort: 8080

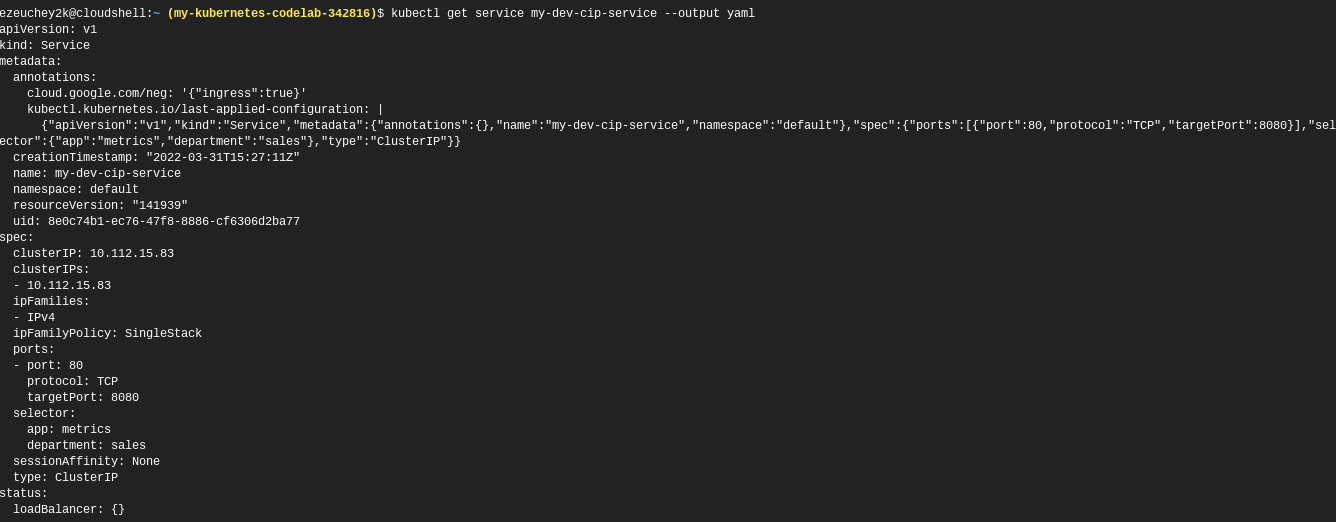

kubectl get service my-cip-service --output yaml to add and display the virtual IP address:

As you can see, the Service has been assigned a ClusterIP of 10.112.15.83.

Accessing Your Service

Now, you should be able to make a request from a pod to your Service by using the cluster IP you generated.

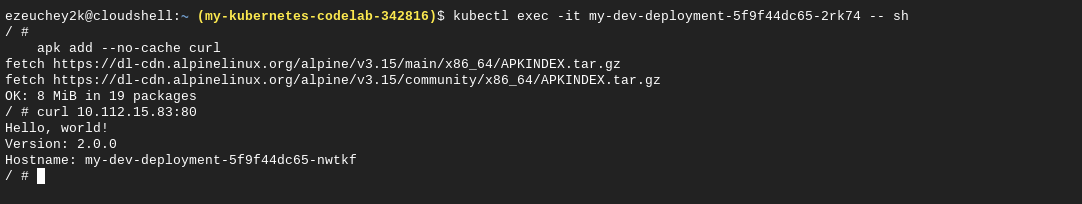

Select a pod from one of those generated from your deployment; then shell into its running container kubectl exec -it my-dev-deployment-5f9f44dc65-2rk74 -- sh.

Once inside the shell, install curl with the command apk add --no-cache curl.

From inside the container, initiate a request to your Service. In the following instance, the cluster IP is 10.112.15.83, and the port declared in the YAML file is 80 (curl 10.112.15.83:80).

With the exception of the LoadBalancer and Headless, all the other Services are derived from the ClusterIP. For instance, NodePort is an extension of the ClusterIP type and, therefore, equally has a cluster IP address.

The LoadBalancer, in turn, is an extension of the NodePort type. Consequently, a LoadBalancer, in addition to having a cluster IP address, also has one or more NodePort values.

External Traffic Networking

From the NodePort, external traffic enters the cluster and is forwarded to a Service. However, in cloud environments, a load balancer is usually the standard way to expose Services externally. The downside is that a LoadBalancer is often an overkill in some configurations since it requires an IP for each Service, which entails added costs and overhead.

One way to resolve these complexities is by using an Ingress. Although Ingress isn’t a Service, like NodePort, it covers HTTP and HTTPS traffic. It also handles load balancing and requires setting up an Ingress controller to route traffic to Services. Unlike LoadBalancer, Ingress allows you to expose multiple services through the same IP address.

The Role of DNS in Kubernetes

The [Domain Name System DNS is at the heart of Service discovery in Kubernetes. Kubernetes configures an internal DNS Service to create DNS records specifically for Services, and every Service in a cluster gets a DNS name.

Instead of reaching a Service with its ClusterIP, you can use a consistent DNS name. When a pod requests a Service, it queries the internal Kubernetes DNS to discover the IP address of the requested Service.

The ExternalName Service uses DNS instead of selectors.

Kubernetes primarily implements its DNS through the Kubernetes DNS service and CoreDNS. The Kubernetes DNS service listens for when the Service and endpoint events from the Kubernetes API are triggered, especially when DNS records are updated. CoreDNS is an alternative to the Kubernetes DNS service. It uses a single container per instance with negative caching enabled by default.

But what happens when a common Service spans multiple clusters? This is where Service DNS records are vital. One example is CNAME, which is an ExternalName Service type that keeps a record of endpoints that share similar Service names.

CNAME provides a mechanism for clusters to communicate with each other externally through cross-cluster Service discovery with federated services.

Conclusion

In this article, you’ve learned about various Kubernetes networking topics ranging from IP address allocation, CNI APIs, Services, DNS, and more.

Kubernetes and container orchestration have become vital aspects of the DevOps workflow. If you want to further improve your continuous integration process, Earthly is the tool for you. It helps you generate repeatable, complex, idempotent container builds between your local development and continuous integration environment, with achievable outcomes.

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.