How and When to Use Kubernetes Namespaces

We’re Earthly. We make building software simpler and faster using containerization. Check it out.

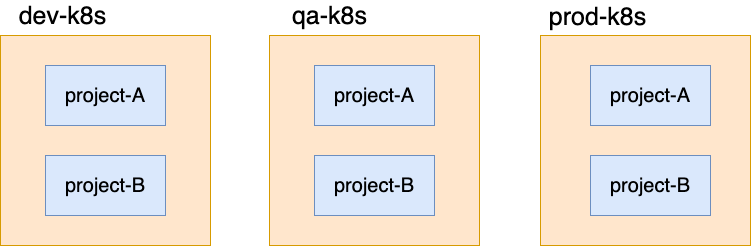

When you start learning about Kubernetes, you quickly learn about the key components that you need in order to run your applications, such as pods, deployments, and persistent volumes, but the components that aren’t absolute necessities often come a little later in your learning journey. One of these components is namespaces, which helps you isolate workloads. This comes in handy when you have several different projects under the same cluster. For example you may have your main application and several internal tools all running together on the same cluster.

In this article, you’ll learn more about what namespaces are, and how they can help you use your resources more efficiently.

Why Use Namespaces?

Probably the most popular reason to use a namespace is that it provides the users a way to separate their applications into separate logical groups. Namespaces are isolated by default, and resources inside a namespace are only able to work with other resources that are also inside the same namespace.

When you first get started working with Kubernetes, it’s tempting to have everything running in the same namespace. Doing this is like running all of your applications on a single server: it’s been done many times before, and it does work, but it’s not recommended.

Running everything alongside each other can be very risky, because it opens you to the possibility that changes to one application will result in changes in another application. This is why you want isolation. Namespaces make it possible to completely separate the resources each application uses. It’s also possible to restrict access based on namespaces, so engineers won’t have access to applications they’re not working on.

What Are Namespaces?

Every resource in Kubernetes lives inside a namespace. At first glance, namespaces themselves may not seem to have much to offer, as separating resources into different logical groups is really the only thing they do natively, but that isn’t to say they’re not useful.

The things you can do with namespaces are incredibly helpful. You can use namespaces to manage permissions, making sure that engineers and managers only have access to the resources that are relevant for them. Namespaces also make it a lot easier to manage resources, because resource names only have to be unique inside of their own namespace, naming conventions are greatly simplified since you don’t need to include the name of the application context in each resource name.

When you want to get started working with namespaces, it’s important to know that there are two primary types of namespaces: default namespaces and custom namespaces.

Default Namespaces

There are three default namespaces that come with any Kubernetes cluster: default, kube-system, and kube-public. The default namespace is where all Kubernetes objects go if no other namespace is specified. When you create a new Kubernetes cluster, this namespace won’t have any resources in it, and is reserved for user-created resources.

The kube-system namespace is one that you’re generally not going to interact with much. It’s used for the processes that make Kubernetes work, like etcd, the kube-scheduler, and other core functions.

The kube-public namespace is one that you may interact with, but primarily just to get information, not to change or create resources inside of. It houses publicly accessible data, like the information needed to communicate with the Kubernetes API.

Depending on the version of Kubernetes that you’re running, you might also see the kube-node-lease namespace, which helps keep track of node heartbeats, which are used to improve scalability and performance.

Custom Namespaces

Custom namespaces are the ones that you, the administrator, create. These are the namespaces you use for the individual applications or the type-specific resources (such as NGINX Controller that you’re running.

While it’s helpful to know about the default namespaces, you’ll be spending most of your time using custom namespaces—or rather, you should be spending most of your time in custom namespaces.

Creating Namespaces

As with most resources inside of Kubernetes, you can create a namespace in two different ways. You can either create it using kubectl or by creating a manifest file that you can then apply.

Using Kubectl

It’s considered best practice to create manifest files and use those to create your resources, as it allows you to track your changes and keep a better overview of your cluster.

Start out by running kubectl get namespaces so you can see the namespaces you have. If you are using a completely new cluster, you should see something resembling the following output:

NAME STATUS AGE

default Active 208d

kube-node-lease Active 208d

kube-public Active 208d

kube-system Active 208dGetting a new namespace created is as simple as running kubectl create namespace <name>, like shown below:

$ kubectl create namespace test

namespace/test created

$ kubectl get namespaces

NAME STATUS AGE

default Active 208d

kube-node-lease Active 208d

kube-public Active 208d

kube-system Active 208d

test Active 8sUsing a Manifest File

As noted, it’s usually more appropriate to create resources like namespaces by using manifest files. This is an example of a simple manifest file to create a Kubernetes namespace:

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Namespace

metadata:

name: production

labels:

name: productionFirst and foremost, you’ll notice the three fields that are needed for every Kubernetes resource; apiVersion, kind, and metadata. These should be fairly familiar to you, as they just provide the information that Kubernetes needs in order to create any resource. Inside the metadata field, you’ll see that a name is defined. This is the name that is shown when you run kubectl get namespaces. Finally, a label of name:production is given as an identifier. To create this namespace you can simply run:

$ kubectl create -f https://k8s.io/examples/admin/namespace-prod.jsonAs you can see, creating namespaces is incredibly simple, but the flexibility and structure it brings to your cluster is incredible.

When to Use Namespaces

There’s no definitive answer as to when namespaces are appropriate, but there is a somewhat general consensus, from which you can then define your own standard. You should create a namespace for every application you’re running. This means that if you have an application that handles authorization, it should be given a namespace; if you have any specific group of resources, like an ingress controller, that should also be given a namespace.

It’s best to try to isolate your resources as much as it makes logical sense to do so. If resources can be grouped under a single definition like a bounded context, then it’s likely those resources should be in their own namespace.

Kubectx + Kubens

Once you get started working with multiple namespaces, you’re likely going to find yourself frequently switching between namespaces. The official way to do it is quite inelegant; if you want to switch to the namespace production inside the current cluster, you would have to type the following:

$ kubectl config set-context --current --namespace=productionAs you can probably tell, not only can it be troublesome to remember the entire command, but also quite frustrating to type out many times throughout a workday.

Thankfully, a team has created the tool kubectx + kubens which makes managing namespaces in Kubernetes much easier. Once you install this tool, you can simply execute kubens <namespace> to switch a given namespace.

If you want to supercharge the utility, you should also install Fzf, a fuzzy finder tool. Once Fzf is installed, you can just execute kubens and it will show you a list of all the available namespaces in your cluster. From here, you can type a partial name to search for namespaces, or you can simply use the arrow keys to navigate through the list.

Conclusion

By now, you should have a good grasp of what namespaces are, what the default namespaces do, and how you can create your own. Additionally, you’ve learned about when you should use namespaces to create a logical separation of your applications and workloads.

If you’re running your applications on Kubernetes and you want a simple and effective way of deploying your application to your clusters, check out Earthly, a tool designed to help with repeatable and easy builds.

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.