Why is JRuby Slow?

Recently, I made some contributions to the continuous integration process for Jekyll. Jekyll is a static site generator created by GitHub and written in Ruby, and it uses Earthly and GitHub Actions to test that it works with Ruby 2.5, 2.7, 3.0, and JRuby.

The build times looked like this:

| Ruby Version | Jekyll CI Time |

|---|---|

| 2.5 | 8m 31s |

| 2.7 | 8m 33s |

| 3.0 | 7m 47s |

| JRuby | 45m 16s |

The Jekyll CI does lots of things in it that a simple Jekyll site build might not but clearly JRuby was slowing the whole process down by a significant amount, and this surprised me: Wasn’t the entire point of using JRuby, and its new brother TruffleRuby, speed? Why was JRuby so slow?

Even building this blog and using all the tricks I’ve found, the performance of Ruby on the JVM still looks like this:

| Runtime | Jekyll Build Time |

|---|---|

| MRI Ruby 2.7.0 | 2.64 seconds |

| Fastest Ruby on JVM Build | 25.7 seconds |

So why is JRuby slow in these examples? It turns out that the answer is complicated.

What Is JRuby?

I was very happy to discover the JRuby project, my favorite programming language running on what’s probably the best virtual machine in the world. - Peter Lind

JRuby is an alternative Ruby interpreter that runs on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). MRI Ruby, also known as CRuby, is written in C and is the standard interpreter and runtime for Ruby.

Install JRuby

On my mac book, I can switch from the MRI Ruby to JRuby like this.

Install rbenv:

brew install rbenvList possible install options:

rbenv install -l Install:

rbenv install jruby-9.2.16.0Set a specific project to use JRuby:

rbenv local jruby-9.2.16.0Why Do People Use JRuby?

OMG #JRuby +Java.util.concurrent FTW! Doing a recursive backtrace through billion+, I've made it 30,000x faster than 1.9.3. 30 THOUSAND.

— /dave/null (@bokmann) September 21, 2013

There are several reasons people might choose JRuby, several of which have to do with performance.

Getting Past the GIL

MRI Ruby, much like Python, has a global interpreter lock. This means that although you can have many threads in a single Ruby process, only one will ever be running at a time. If you look at many of the benchmark shout-out results, parallel multi-core solutions dominate. JRuby lets you sidestep the GIL as a bottleneck, at the cost of having to worry about writing thread-safe code.

Library Access and Environment Access

A common driver for JRuby usage is the need for a Java-based library or the need to target the JVM. You could be trying to write an Android app or a Swing app using JRuby, or maybe you already have an existing Ruby codebase but need it to run on the JVM. My 2 cents is that if you start from scratch and need to target the JVM, JRuby should not be the first option you consider. If you do choose JRuby, be warned that you will need a good grasp of Java, the JVM, and Ruby: if you’re coming to the JVM for java libraries and functionality, then JRuby won’t save you from having to read Java.

Long-Running Process Performance

MRI Ruby is known to be slow, as compared to the JVM or even Node.js. According to The Computer Language Benchmarks Game, it’s often 5-10x slower than a similar Java solution. Small performance benchmarks are often not the best way to assess practical performance, but one place the JVM is known to perform very well compared to interpreted languages is in long-running server applications, where adaptive optimizations can make a big difference.

Why Is my JRuby Program Slow?

The JVM might be fast at running Java in benchmark games, but that doesn’t necessarily carry over to JRuby. The JVM makes different performance trade-offs than MRI Ruby. Notably, an untuned JVM process has a slow start-up time, and with JRuby, this can get even worse as lots of standard library code is loaded on start-up. The JVM starts by working as a byte code interpreter and compiles “hot” code as it goes but in a large Ruby project, with lots of gems, the overhead of JITing all the Ruby code to bytecode can lead to a significantly slower start-up time.

If you are using JRuby at the command line or starting lots of short-lived JRuby processes, then it is likely that JRuby will be slower than MRI Ruby. However, the JVM is extensively tunable, and it’s possible to tune things to behave more like standard Ruby. If you want your JRuby to behave more like MRI Ruby, you probably want to set the --dev flag. Either like this:

ENV JRUBY_OPTS="--dev"OR

jruby --dev file.rbIn my Jekyll use case, this change and some other small JVM parameter tweaking made a big difference. I was able to get the build time down from 45m 16s to 24m 1s.

| JRuby Flags | Jekyll CI Run Time |

|---|---|

| JRuby | 45m 16s |

| JRuby –dev | 24m 1s |

--dev gets us closer to MRI Ruby

Inside --dev

The --dev flag indicates to JRuby that you are running it in as a developer and would prefer quick startup time over absolute performance. JRuby, in turn, tells the JVM only do a single level jit (-J-XX:TieredStopAtLevel=1) and to not worry about verifying the bytecode (-J-Xverify:none). More details on the flag can found on hedius’s blog.

Why Is my JRuby Program Wrong?

Ruby’s built-in types were built with the GIL in mind and are not thread-safe on the JVM. If you move the JRuby to sidestep the GIL, keep in mind that you may be introducing threading bugs. If you get unexpected or non-deterministic results in your concurrent array usage, you should look at concurrent data structures for the JVM like ConcurrentHashMap or ConcurrentSkipListMap. You may find that they not only fix the threading issues but could be orders of magnitude faster than the idiomatic Ruby way. Jekyll is not multi-threaded, however, so this is not an issue I needed to worry about.

What Is TruffleRuby?

GraalVM is a JVM with different goals than the standard Java virtual machine.

According to Wikipedia, these goals are:

- To improve the performance of Java virtual machine-based languages to match the performance of native languages.

- To reduce the start-up time of JVM-based applications by compiling them ahead-of-time with GraalVM Native Image technology.

- To allow freeform mixing of code from any programming language in a single program.

Increased performance and better start-up time sound precisely like what we need to improve on JRuby, and this fact did not go unnoticed: TruffleRuby is a fork of JRuby that runs on GraalVM. Because GraalVM supports both ahead of time compilation and JIT, it’s possible to optimize either for peak performance of a long-running service or for start-up time, which is helpful for shorter running command-line apps like Jekyll.

TruffleRuby explains the trade-offs of AOT vs. JIT like this:

| Configuration: | Native (--native, default) |

JVM (--jvm) |

|---|---|---|

| Time to start TruffleRuby | about as fast as MRI start-up | slower |

| Time to reach peak performance | faster | slower |

| Peak performance (also considering GC) | good | best |

| Java host interoperability | needs reflection configuration | just works |

Install TruffleRuby

Install rbenv:

brew install rbenvList possible install options:

rbenv install -l Install:

rbenv install truffleruby+graalvm-21.0.0

rbenv local truffleruby+graalvm-21.0.0 ruby --version

truffleruby 21.0.0, like ruby 2.7.2, GraalVM CE Native [x86_64-darwin]Set mode to --native

ENV TRUFFLERUBYOPT='--native'Performance Shoot-Out

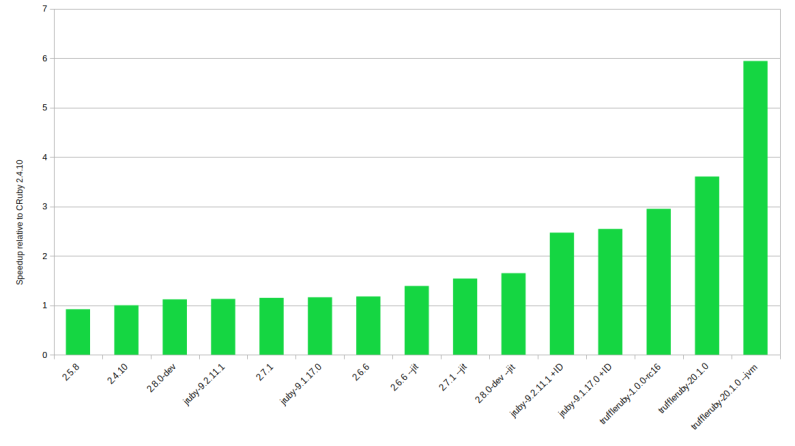

TruffleRuby is significantly better in CPU heavy performance tests than JRuby, whose performance is significantly better than MRI Ruby. PragToby has a great breakdown:

However, in my testing with Jekyll, and the Jekyll CI pipeline, JRuby, and TruffleRuby are significantly slower than using MRI Ruby. How can this be?

I think there are two reasons for this:

- Real-World projects like Jekyll involve a lot more code, and JITing that code has a high start-up cost.

- Real-world code like Jekyll or Rails is optimized for MRI Ruby, and many of those optimizations don’t help or actively hinder the JVM.

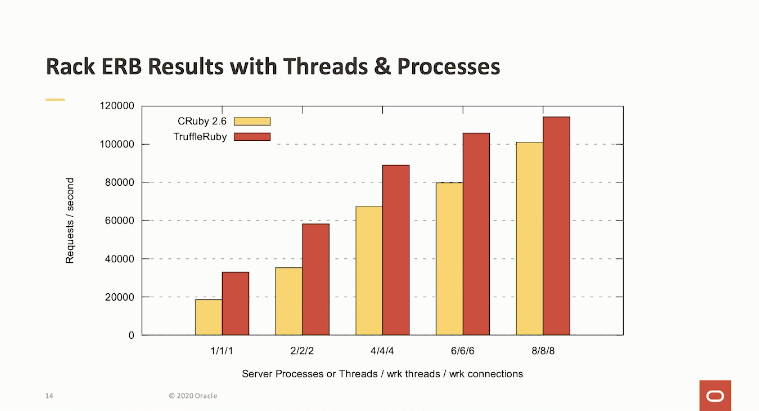

Failure of Fork

The most obvious place where you see this difference is multi-process Ruby programs. The GIL is not an issue across processes and the comparatively fast start time of MRI Ruby is an advantage when forking a new process. On the other hand, JVM Programs are often written in a multi-threading style where code only has to be JIT’d once, and the start-up cost is shared across threads. And in fact, if you ignore language shoot-out games, where everything is a single process and instead compare an MRI multi-process approach to a TruffleRuby multi-threading approach, many advantages of the JVM seem to disappear.

This chart comes from Benoit Daloze1, the TruffleRuby lead. The benchmark in question is a long-running server-side application using a minimal web framework. It is in the sweet spot of the Graal and TruffleRuby, with little code to JIT and much time to make up for a slow start. But even so, MRIRuby does well.

Which brings me back to my original question: Why is JRuby slow for Jekyll? I do not see similar times but significantly slower times. Jekyll is not forking processes, so that is not the issue. hugo, the static site builder for Go, is significantly faster than Jekyll. So we know that Jekyll is not at the limits of hardware where there is simply no more performance to squeeze out.

Test With RubySpy

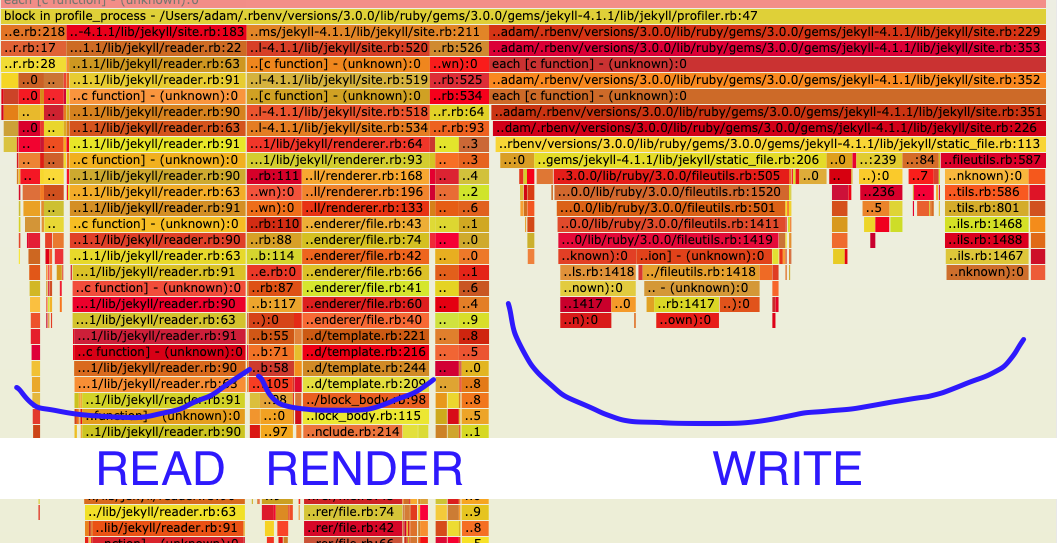

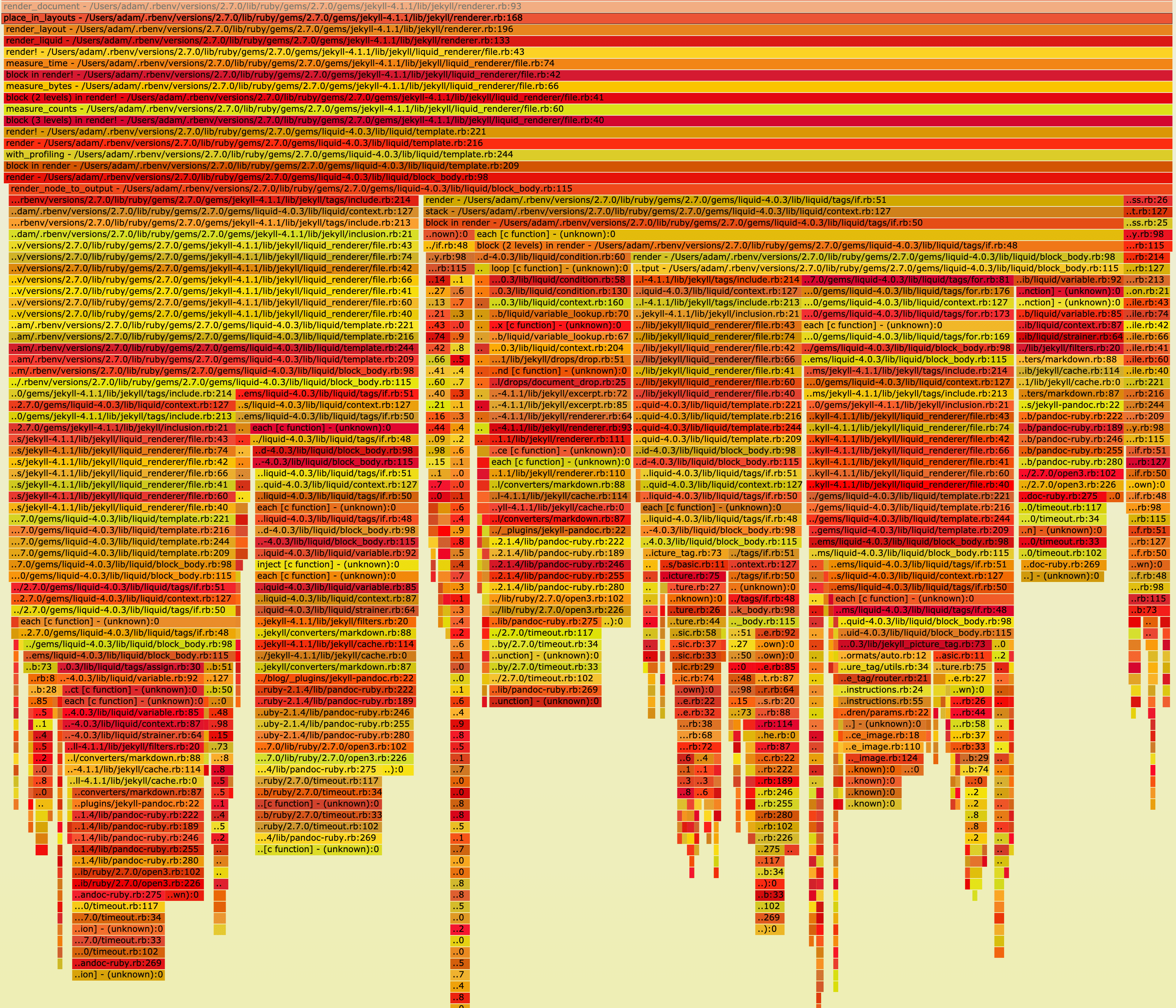

To dig into this, let’s take a look at a flame-graph of the Jekyll build for this blog using RubySpy:

| Runtime | Jekyll Build Time for this site |

|---|---|

| MRI Ruby 2.7.0 | 2.64 seconds |

| TruffleRuby-dev | 25.7 seconds |

Jekyll Test 1

sudo RUBYOPT='-W0' rbspy record -- bundle exec jekyll build --profile

What we see is that 50% of the wall time was spent in writing files:

# Write static files, pages, and posts.

#

# Returns nothing.

def write

each_site_file do |item|

item.write(dest) if regenerator.regenerate?(item)

end

regenerator.write_metadata

Jekyll::Hooks.trigger :site, :post_write, self

endAnd 16% of time was spent reading files.

# Read Site data from disk and load it into internal data structures.

#

# Returns nothing.

def read

reader.read

limit_posts!

Jekyll::Hooks.trigger :site, :post_read, self

endOverall only 22% of the time was spent doing the actual work of generating HTML:

# Render the site to the destination.

#

# Returns nothing.

def render

relative_permalinks_are_deprecated

payload = site_payload

Jekyll::Hooks.trigger :site, :pre_render, self, payload

render_docs(payload)

render_pages(payload)

Jekyll::Hooks.trigger :site, :post_render, self, payload

endIn other words, all the time is spent reading to and from the disk. Clearly, the hugo case shows us this could be faster: we aren’t hitting a hardware limit. Yet why does this run even slower in JRuby and TruffleRuby than it does in MRI Ruby? Let’s try another test.

Jekyll Test 2

Testing on the build process for another Jekyll site gives similar results timings: TruffleRuby is significantly slower.

| Runtime | Jekyll CI Run Time |

|---|---|

| MRI Ruby 2.7.0 | 20 seconds |

| TruffleRuby-dev | 116 seconds |

This time the flamegraph shows most time is spent with rendering liquid templates rather than IO. I wasn’t able to figure out a way to get a flamegraph out of TruffleRuby.

So what does this mean? My guess is that the filesystem Ruby code or the liquid templates do not benefit from being on the JVM. On the contrary, they seem to run slower.

It might be possible to reimplement write and read to follow JVM high-performance file access best practices, and it might be possible to reimplement liquid templates in a Java native way. That should bring a speed-up, but I’m not sure if that would make JRuby faster than MRI Ruby for Jekyll or only bring it up to a similar performance.

Performance Advice

All this leaves me with the most generic performance advice: You should test your Ruby codebase with different runtimes and see what works best for you.

If your code is long-running, CPU bound, and thread-based, and if the GIL limits you, TruffleRuby will probably be a win. Also, if that is the case and you tweak your code to use Java concurrent data structures instead of Ruby defaults, you can probably achieve an order of magnitude speed-up. If the garbage collector is a bottleneck for your app, that could also be another reason for trying out a different runtime.

However, if your existing ruby codebase is not CPU bound and not multi-threaded, it will probably run slower on JRuby and Truffle Ruby than with the MRIRuby runtime.

Also, I could be wrong. If I missed something important, then I’d love to hear from you. Here at Earthly we take build performance very seriously, so if you have additional suggestions for speeding up Ruby or Jekyll, I’d love to hear them.2

Updates

Update #1

Both @ChrisGSeaton, the creator of TruffleRuby and @headius, who works on JRuby have responded on reddit with suggestions and requests for reproduction steps. I’m going to put together an example to share.

Update #2

The area where JRuby and TruffleRuby shine are long running processes that have had time to warm up. Based on suggestions I put together a repository of a simple small Jekyll build being built 20 times by the same process on GitHub. After 20 builds with the same running process the build times do start to converge, but even after that MRI Ruby is still fastest.

Update #3

I have filed a bug with Truffle Ruby and received some performance advice that I think is worth sharing here:

Some Feedback on The Assumptions of The Article

Hello there, here are some notes on the blog post.

“TruffleRuby is a fork of JRuby”

Technically true from a repository point of view, and that’s what the README says (I’ll update that), but in practice it’s like >90% of code is not from JRuby. It’s quite different technologies.

“hugo, the static site builder for Go, is significantly faster than Jekyll. So we know that Jekyll is not at the limits of hardware where there is simply no more performance to squeeze out.”

I’d bet that’s in part due to a different design. Most likely hugo is better optimized and might do much less work due to different constraints.

“However, if your existing ruby codebase is not CPU bound and not multi-threaded, it will probably run slower on JRuby and TruffleRuby than with the MRI Ruby runtime.”

I think there is no such simple rule and also there is the question of “not CPU bound” is how much time spent in the kernel. TruffleRuby can be faster on many Ruby workloads, as long as there is Ruby code to run, there is potential for optimization. Of course if 90% is spent in read/write system calls, only 10% of it can be optimized by a Ruby implementation, but I would expect that’s pretty rare.

The main thing I think is if it’s not almost entirely IO-bound, then there is potential to speed up. And the only way to know for sure is to try it, as you say.

“I’d especially love to hear how to get a flame graph out of TruffleRuby”

Thank you for the issue at https://github.com/oracle/truffleruby/issues/2363. Currently TruffleRuby has multiple Ruby-level profilers (

--cpusampler, VisualVM, Chrome Inspector). We’re working on having an easy way to get a flamegraph (right now we use this but one needs to clone the TruffleRuby repository which is less convenient). Java-level profiling is also possible via VisualVM. async-profiler needs something like JDK>=15 to work properly with Graal compilations IIRC.

Some Advice for Making Ruby Single Process

Your simplest answer for both JRuby and TruffleRuby would be to set it up to use a single process to do everything. In JRuby, it is trivial to start up a separate, isolated JRuby instance within the same process:

my_jruby = org.jruby.Ruby.new_instance my_jruby.eval_script(ruby_code)The code given will run in the same process but a completely different JRuby environment. This can be adapted to run your “subprocesses” without starting a fresh JVM every time.

TruffleRuby likely has something similar based on GraalVM polyglot APIs.

If you managed to get your CI run to use a single process, I would be surprised if it was not as fast or faster than standard C-based Ruby.

Note: The article does cover --dev and I did put together a single process example in update 2. The results are way better, but still slower.

Using Application Class Data Sharing

AppCDS is a way to significantly improve startup speed without impacting total runtime performance. It’d be interesting to see if employing that helps with performance. https://medium.com/@toparvion/appcds-for-spring-boot-applications-first-contact-6216db6a4194

Finally, if you can, I’d be interested to see what happens if you work from a RAMDisk rather than the HD. I imagine the IO problems you were likely seeing is due to a lot of back and forth communication between the app and the disk, what happens if you kill that off?

The feedback from the JRuby and TruffleRuby people has been amazing. They have been offering suggestions and asking for tickets and reproduction steps. These are ambitious projects that keep improving and I’m excited to hear that making Jekyll run faster than it does on CRuby is very possible with some additional elbow grease.

More Resources

The work behind JRuby, TruffleRuby, and especially GraalVM is terrific. The TruffleRuby benchmark numbers for CPU heavy work continue to improve year upon year. I’m not trying to dunk on the great work done, merely trying to investigate the numbers I am seeing.↩︎

I’d especially love to hear how to get a flame graph out of TruffleRuby. I didn’t get anywhere getting async-profiler to attach.↩︎