Creating a G++ Makefile

We’re Earthly. We make building software simpler and therefore faster using containerization. This article covers GNU’s gcc compiler. If you’re interested in an approach to builds that allows you to keep gcc and build everywhere then check us out.

C++ is one of the most dominant programming languages. Although there are many compilers available, GCC still ranks as one of the most popular choices for C++. GCC is part of the GNU toolchain, which comes with utilities like GNU make, GNU bison, and GNU AutoTools.

What Is GCC?

GNU Compiler Collection, also known as GCC, started as a C compiler, created by Richard Stallman in 1984 as a part of his GNU project. GCC now supports many languages, including C++, Objective C, Java, Fortran, and Go. The latest version as of writing this article is GCC 11.1, released April 27, 2021.

The C++ compiler of GCC is known as g++. The g++ utility supports almost all mainstream C++ standards, including c++98, c++03, c++11, c++14, c++17, and experimentally c++20 and c++23. It also provides some GNU extensions to the standard to enable more useful features. You can check out the detailed standard support on gnu.org.

In this tutorial, you will learn how to compile C++ programs with the g++ compiler provided by GCC, and how to use Make to automate the compilation process.

Installing GCC

I’ll touch briefly on installing for Linux, Mac, and Windows.

Linux

GCC is one of the most common tools in the unix world, and is available in every single Linux distribution. Here, I show you how to install the GNU toolchain for some famous distributions.

For Ubuntu, you need to run the following command:

sudo apt update && sudo apt install build-essentialsFor Arch Linux, run:

sudo pacman -S base-develFor Fedora, run:

dnf groupinstall 'Development Tools'For other distributions, consult the official wiki of your distribution.

Mac

To install GCC on Mac, run brew install gcc which will place g++-11 in /usr/local/bin. Then create an alias to g++: alias g++='g++-11'.

Windows

To use GCC in Windows, use WSL2. You can install GCC inside the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) and use it from there.

Compiling With G++

Let’s take a look at how the compilation with G++ works. You will compile a simple Hello, World! program. Save the following file as hello.cpp:

#include<iostream>

int main() {

std::cout << "Hello, World!" << std::endl;

return 0;

}To compile this file, simply pass this file to g++:

g++ hello.cppBy default, g++ will create an executable file named a.out. You can change the output file name by passing the name to the -o flag.

g++ -o hello hello.cppThis will compile hello.cpp to an executable named hello. You can run the executable and see the output:

./helloThe Compilation Process

Although the compilation can be done with one command, the compilation process can be divided into four distinct phases:

- Preprocessing

- Compilation

- Assembly

- Linking

In the preprocessing part, the GNU preprocessor (cpp) is invoked, which copies the header files included via #include, and expands all macros defined with #define. You can perform this step manually by running the cpp command.

cpp hello.cpp > hello.iThe file hello.i contains the preprocessed source code.

In the next phase, the g++ compiler compiles the preprocessed source code to assembly language. You can run this step manually with the following command:

g++ -S hello.iThe -S flag creates a file hello.s, which contains the assembly code.

In the next step, the assembler as converts the assembly to machine code.

as -o hello.o hello.sFinally, the linker ld links the object code with the library code to produce an executable.

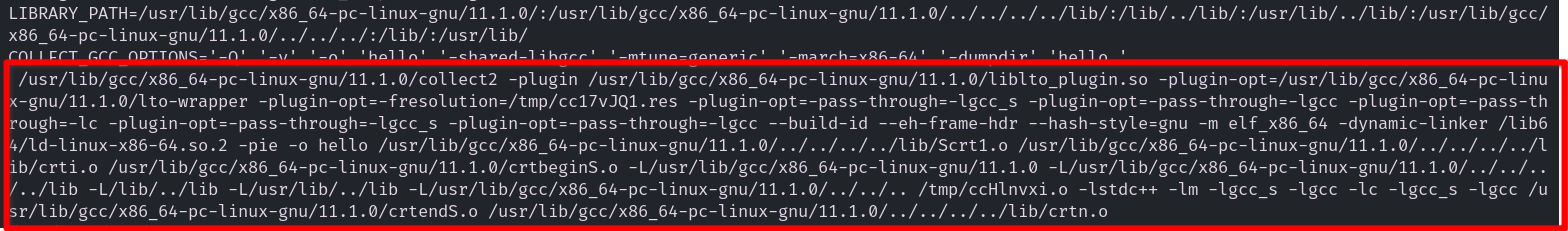

ld -o hello hello.o ...libraries...The libraries argument above is a long list of libraries that you need to find out. I omitted the exact arguments because the list is really long and complicated, and depends on which libraries g++ is using on your system. If you are interested to find out, you can run the command g++ -Q -v -o hello hello.cpp and take a look at the last line where g++ invokes collect2

Thankfully, you do not have to perform these steps manually, as invoking g++ itself will take care of all these steps.

Using the make Utility

Even though the compilation commands have been simple so far, this is not necessarily the case when you have multiple source files. As an example, consider this program:

#include "func.h"

int main() {

func(10);

func(100);

return 0;

}hello.cpp

This file includes func.h, which contains the declaration for a simple function:

#ifndef MAKE_GPP_FUNC

#define MAKE_GPP_FUNC

#include<iostream>

void func(int i);

#endiffunc.h

Finally, the definition of func resides in func.cpp:

#include "func.h"

void func(int i) {

std::cout << "You passed: " << i << std::endl;

}func.c

In order to compile your program, you need to compile both hello.cpp and func.cpp, since the former depends on the latter.

g++ -o hello hello.cpp func.cppIf you have more files, then you need to list all of them, while taking care to set the correct include paths and library paths. Moreover, if your code uses any library, you need to list those libraries, too. The resultant command is likely massive and difficult to remember and type. Also, the compilation command will compile all of the source files every time it is executed. But if some of the source files haven’t been modified since the last compilation, it’s a waste of time and resources to compile all the files. But keeping track of what has changed manually is also a difficult task.

This is where the make utility helps. make lets you define your target, and how to reach the target and what are the dependencies. Then it automatically keeps track of which dependencies have changed and recompiles only the necessary parts.

So let’s see how you can utilize make.

The Makefile

In order to let make know what to do, you need to create a file named Makefile in the root of your project. This file can also be named makefile but is traditionally named Makefile so that it appears near other important files such as README.

Create an empty Makefile in the project root and run the command make from the project directory. You should see the following output:

make: *** No targets. Stop.It means make has found the Makefile, but since it is empty, it doesn’t know what to do.

Now let’s see how you can utilize Makefile to tell make what to do. The Makefile consists of a set of rules. Each rule has three parts—a target, a list of prerequisites, and a recipe—like this:

target: pre-req1 pre-req2 pre-req3 ...

recipes

...Note that there are tabs before the recipe lists. You can’t use any other whitespace character. You must use tabs.

When make executes a target, it looks at its prerequisites. If those prerequisites have their own recipes, make executes them and when all the prerequisites are ready for a target, it executes the corresponding recipe for the current target. For each target, the recipes are executed only if the target doesn’t exist or the prerequisites are newer than the target.

Let’s update the Makefile for the example program:

all: hello

hello: hello.o func.o

g++ -o hello hello.o func.o

func.o: func.cpp func.h

g++ -c func.cpp

hello.o: hello.cpp

g++ -c hello.cppNow, run the make command again. You should see the commands being run by make:

g++ -c hello.cpp

g++ -c func.cpp

g++ -o hello hello.o func.oAnd you’ll notice that an executable called hello has been created in the directory. So, how did make do that? Let’s analyze.

When you run make without any arguments, it executes the first target. In the Makefile, the all target has a prerequisite hello. So, make looks for a rule to create hello. The rule hello has two prerequisites hello.o and func.o. Now, the target hello.o depends on hello.cpp which exists and is newer than the target hello.o (which does not exist). So, make now executes the recipe for hello.o and runs the command g++ -c hello.cpp. This creates the hello.o file.

Now make starts resolving func.o. Both of its pre-requisites exist and are newer than the target. So make executes the command g++ -c func.cpp. Now that the target hello has both the prerequisites satisfied, its recipe can be executed and the hello file is created.

Now what happens if one of the files is changed? Let’s change the hello.cpp file and change the func(10) line to func(20):

#include "func.h"

int main() {

func(20);

func(100);

return 0;

}Now if you run make, you’ll notice that it does not execute all the steps:

g++ -c hello.cpp

g++ -o hello hello.o func.oThis time, make does not compile func.c because the file func.o exists, and its prerequisites are not newer than itself. This is because you have not changed func.cpp or func.h.

On the other hand, the file hello.cpp is newer than hello.o. So it needs to be recompiled, and when hello.o is re-created, the target hello needs to be executed, since it depends on hello.o.

You can also call make with the name of a specific rule. For example, running make func.o will only run the rule for func.o

Comments in Makefile

You can have comments in Makefile, which start with a # and last till the end of the line.

all: hello # This is a comment

hello: hello.o

...Using Variables

Observe that in your Makefile, there are quite a lot of repetitions. For example:

func.o: func.cpp func.h

g++ -c func.cppIn this rule, we have the string func repeated four times. Since here the base name of the source file and the compiled file are the same (func), we can use variables to tidy up the rules. The variables not only make the Makefile cleaner, they can be overridden by the user so that they can customize the Makefile without editing it.

A variable in Makefile starts with a $ and is enclosed in parentheses ()or braces {}, unless it’s a single character variable.

To set a variable, write a line starting with a variable name followed by =, := or ::=, followed by the value of the variable:

objects = hello.o func.oHere the variable objects is set to hello.o func.o. Now whenever you use this variable in a rule, it will be replaced by its value.

objects = hello.o func.o

all: hello

hello: $(objects)

g++ -o hello $(objects)This is the same as writing:

hello: hello.o func.o

g++ -o hello hello.o func.oThere is another way of defining variables using the ?= operator. This defines the variable only if it has not been defined before.

When you invoke make, it converts all the environment variables available to it with a make variable with the same name and value. This means you can set variables using environment variables. Also, you can override any variable by passing them while invoking make. For example, the g++ command can be invoked through a variable.

CXX = g++

objects = hello.o func.o

all: hello

hello: $(objects)

$(CXX) -o $(objects)Now running make will compile the files with g++. However, the user can now substitute alternative if they want to.

make CXX=clang++Now the files will be compiled by clang++ since CXX=clang++ overrides the variable CXX defined in the Makefile.

Phony Target

So far, you have only created files, but make can also “clean” files. Usually it’s a good idea to have a clean target to delete all the generated files, basically returning the project to a clean slate.

Here is an example for your Makefile:

clean:

rm *.o helloYou can run it via make clean. This cleans all the .o files and the hello file. Because the rm command does not create a file named clean, the rm command will be executed every time you invoke make clean.

But if you ever create a file called clean in the directory, make will get confused. Since the clean file is there, and the clean target has no prerequisites, it is always considered to be newer than its prerequisites. Therefore, the recipe will not run.

The same problem will arise with the all target if there is ever a file named all. To fix this, you can declare the targets to be “phony”.

.PHONY: all clean

clean:

rm *.o helloConclusion

Makefile is one of the most important components of compiling C++ using g++. It makes compilation easy and predictable and also saves time and resources by compiling only the necessary files. In this tutorial you learned how to install g++, and compile C++ programs with g++. You also learned how to write Makefiles and utilize make for increased productivity and automation.

Because make is a feature rich utility and supports a wide range of systems, it has a steep learning curve. As your project grows in size, the Makefile also grows in complexity.