Docker vs. Virtual Machine: What Are the Differences?

We’re Earthly. We make building software simpler and faster using containers. If you’re grappling with Docker containers vs VMs, Earthly certainly help on the container side. Give it a go.

Docker and similar containerization technologies have taken the tech world by storm. They have largely displaced virtual machines (VMs) as the de facto segmentation methodology for servers and software developer workflows. However, it’s important to note that Docker containers and VMs do not make for an apples-to-apples comparison. One is not inherently better than the other, with each having its pros and cons and use cases that might be better suited to one than the other.

In this article, you will see a breakdown of these two virtualization technologies. We’ll highlight the strengths and limitations of each by focusing on various factors such as interaction with the host machine, ease of use for the user, performance, security, and ease of replicability.

Host Machine Utilization

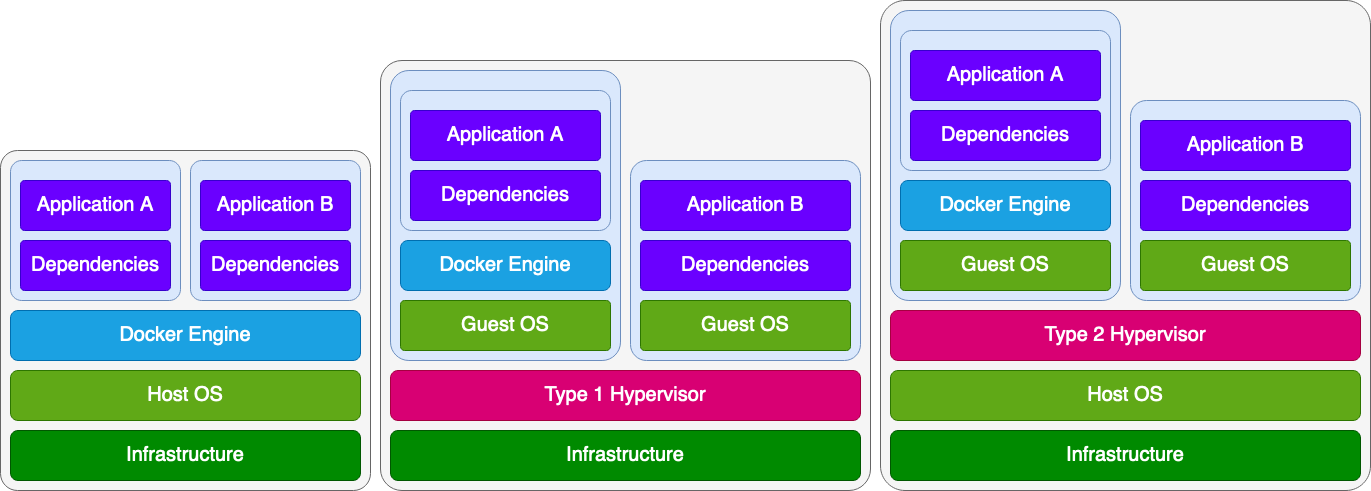

The primary differentiator between VMs and containers is their interaction with the host machine. Virtual machines run under a particular program called a hypervisor, which is traditionally categorized as one of two types. Type 1 hypervisors (also known as bare-metal hypervisors) run directly on the host infrastructure, whereas the arguably more beginner-friendly Type 2 hypervisors run under the host’s own operating system (OS). In both cases, the hypervisor manages VMs that contain their fully-fledged OS and kernel. This leads to extensive segmentation between the host and the VM, but hardware access is now virtualized due to this additional abstraction. This can potentially lead to performance losses as compared to native workloads.

Containers work differently by comparison. Container engines, like Docker, run atop the host OS, similar to Type 2 hypervisors; but unlike VMs, containers do not have their own OS and instead utilize the host’s kernel. This means that Docker does not need to emulate hardware resources and can instead allow the containers to have potentially native hardware performance levels.

It is important to note that these technologies are not mutually exclusive and can work together. Indeed, if you were to run Docker containers in the cloud with Amazon Web Services (AWS), the host, in that case, would likely be a VM itself, provisioned through Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2) or a similar service.

Simplicity

In terms of simplicity, there are a few things to consider. VMs are easy to reason about from an abstract conceptual standpoint, as users can easily compare them to traditional machines. Most hypervisors, like VirtualBox, Hyper-V, and Proxmox, will allow you to configure VMs using terminology analogous to real machines, such as CPU cores and RAM. Although the underlying implementations are undoubtedly quite complex, beginners can still straightforwardly interface with them thanks to this understanding.

On the other hand, containers are a bit harder to understand, especially if you are new to the concept. Although awareness and a general understanding of containers are getting better by the day, when Docker first started making waves in the tech scene, containers were often likened to “lightweight VMs”. This conflation is easy to make when they seem to achieve similar outcomes; however, it is not really accurate. Although the outcome is relatively similar, the design goals and implementations are worlds apart.

However, once a user becomes more familiar with containerization and overcomes the initial learning curve, day-to-day use of Docker can be quite simple. This is further eased by the wealth of excellent documentation and resources online for Docker and related tools. While similar documentation and resources exist for VMs, each implementation differs slightly, making the resources less ubiquitous.

Although there are multiple container engines besides Docker, such as Podman, most of them implement the Open Container Initiative (OCI) specification, meaning that there is a measure of interoperability between them. Indeed, certain tools (like Podman) even reimplement the command line API to allow for ease of migration and maximal reverse compatibility with users making the change from Docker. As a result, Docker resources tend to be quite ubiquitous and applicable to many systems.

Speed

VM performance is influenced by a number of factors, such as the type of application being run in the VM, the guest OS of the VM, resource allocations, and the hypervisor itself. Typically, CPU-bound applications can experience near-native performance when running in a VM, provided they have adequate resource allocations for things like memory and storage—such that they do not suffer from bottlenecks in those areas from the overhead of the OS and any other applications running on the VM. A well-configured VM running a lightweight OS (such as an Ubuntu Server) and focusing on a single workload (such as a web server) can achieve very satisfactory results. However, because of the multitude of configuration options, there can be a lot of room for operator error and misconfiguration before you even start considering all the discrete differences between various hypervisor and guest OS combinations.

Containers can have a number of performance benefits when compared to VMs. They tend to start up faster—typically in a matter of seconds—whereas VMs often take a couple of minutes to fully initialize and boot (again, varying heavily depending on the workload). Containers also make better use of the host’s resources, only taking what they need and then releasing it when they are done. While some hypervisors offer features like dynamic resources that scale up and down depending on what the VM needs, there is typically a minimum resource allocation that the VM will consume even when it is idle.

As previously mentioned, containers share the kernel of the underlying host OS. This means that fewer redundant components are running as compared to VMs, which need to run a full OS of their own, even if the OS they are running is the same as the host. These benefits all compound to make containers a compelling lightweight offering. That being said, it is not clear-cut that you can say, “containers are better,” as a well-configured VM can also achieve near-native performance. Ultimately, it will come down to the particular use case and the need for either container-style environment segmentation or full VM-style segmentation.

Security

When it comes to security, VMs have a lot going for them. One of the key traits of VMs is the fact that the hypervisor enforces segmentation at a lower level than the guest OS. This makes it quite difficult (though not impossible) for untoward issues to occur—issues where guest VMs can access things that the administrator would prefer that they do not. As VMs emulate an entire system, they are typically susceptible to any attacks that a real computer would be.

Because of this, as well as the fact that the VM has its own OS, it is crucial to ensure that proper security measures are taken on all VMs, that they are suitably patched, and ultimately, that they are treated like real physical machines as far as security is concerned. One other thing to be aware of is the risk of VM escape attacks. This is a type of attack where a malicious program is able to somehow bypass the hypervisor’s segmentation and gain some measure of access to either the hypervisor, host, other VMs, or the host’s hardware. VM escape attacks are arguably quite rare, but they can happen.

On the other hand, Docker containers are somewhat more susceptible to escape attacks due to weaker segmentation. Unfortunately, Docker’s proximity to the host OS does put it in a worse starting position in terms of security, but steps can be taken to mitigate a lot of the risk. For instance, rather than running containers with the default root users, it is advisable to run them with an unprivileged user to help mitigate privilege escalation and attacks. It is also always a good idea to either build your own images or carefully review any other images you use. It is all too common for seemingly helpful images on public registries, like Docker Hub, to actually be malicious, so take the time to check what is in your images before running them.

Ease of Replicability

An important aspect of any virtualized deployment is replicability—the ability to perfectly copy and reproduce a given deployment. VMs are inherently flawed in this regard, as they are not idempotent, nor are they intended to be.

Thankfully, there are tools and features that can eliminate a lot of this uncertainty for VMs, starting with the hypervisor itself. Most hypervisors will provide the operator with a way to take a snapshot of a VM, saving its current state so that it can be reapplied later. This is in addition to the duplication and cloning features offered by many hypervisors, but you should use such functionality with care. Cloning a fully emulated system can lead to issues if you plan to run the clone in the same space as the original, as there can be conflicting hostnames and other such configuration mishaps manifesting as issues that are difficult to debug.

Another approach that helps to solve this issue is to use orchestration tools, like Ansible, which allows you to execute playbooks against servers to move them toward the desired state. It is not uncommon for administrators to use tools like Ansible to set up all the software dependencies needed for a VM to run its intended workload.

Docker containers have arguably more desirable behavior in this regard, as they should work the same way on every host. In practice, there can be strange issues, like different Docker versions and odd environmental configurations that lead to differences between how containers behave on different hosts, but these issues are quite rare. The process of building a Docker image itself is ideally idempotent. It should always give the same output (it is possible to have non-idempotent builds if you try, but you should avoid this). This is a boon for replicability, as it means that with nothing more than a Dockerfile, two developers should be able to build and run the same image and container, no matter how different their workstations happen to be—aforementioned rare issues notwithstanding.

Conclusion

Now that you have seen how VMs and Docker containers compare, it should be clear that each technology shines in its own way, and which one is right for you will largely depend on what you want to do with it. However, both are perfectly capable, with careful configuration, and there is no reason you cannot use the two in conjunction if that will give you the best result in your own situation.

If you like Docker’s excellence when it comes to replicability and find yourself frustrated over hard-to-replicate issues with your CI/CD pipelines, be sure to consider Earthly.dev. Earthly.dev allows you to easily define repeatable builds that work the same locally as in the cloud, streamlining the CI development and debugging process, and saving you from endless fix ci commit messages.

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.