Career Advice: Be Confidently Uncertain

We’re Earthly. We make building software simpler and therefore faster using containerization. Give us a go.

“OH GAWD”

Around the time of the subprime mortgage collapse, I was working in an enterprise software company. I worked in a large open space full of cubicles. Several times a week, I would hear a slightly panicked voice say, “oh god!”

It was always the same voice, and always said in the same way: “OH GAAAHWD”. I don’t think it was said loudly, but it had this tone of distress that always caught my ear.

That was Alex1, and she wasn’t watching the stock market. She had just gotten feedback on her work. Either a ticket had just been set back to ‘in progress’ or someone from QA had shown up at her desk to ask a question (which implied something was wrong).

Alex was not confident in her work and panicked at the sign of negative feedback.

Quality Was Assured

About the company, well it was great. But the software was a bit ugly. It had a million features when I started and we just kept adding more. The trick was ensuring your new feature didn’t cause strange interactions with any of the existing features.

We rarely did code reviews or automated testing, but man, we could write legacy code at an astounding pace. And the thing keeping the product from falling apart under the weight of all the new features was Quality Assurance. They controlled the release branch. And Alex was afraid of them failing her work.

“These Are the Requirements!”

Amy was a more senior developer at the same place. One of the two most senior software engineers at the company. Today Amy would be a principal engineer, but we didn’t have those titles.

Anyhow, Amy would get push back on features from QA as well. Less often, but it still happened. Amy was never afraid, though. Amy was so confident in her work, that if there was a problem, you couldn’t call it that. You had to hint that maybe someone could possibly consider improving things a bit before the feature was released.

If you didn’t adopt that tone and you insisted Amy did something wrong, she would lift this blank piece of paper she kept on her desk into the air and say “These were the requirements!” This was a shorthand for “How can it be broken when it matches the non-existant requirements!” which was a shorthand for “That’s not a bug, it’s a feature!” That would be the end of the discussion.

Sometimes if you’re talented, you can get away with arrogance.

Here is my question: How confident should you be about yourself to succeed. Where should you aim for on a spectrum from Oh-God-Alex to Thats-A-Feature-Not-A-Bug-Amy?

Clearly, Alex didn’t inspire confidence in her coworkers. The Bosses wouldn’t give high impact projects to Alex. And yet dealing with Amy’s excessive confidence is a bit much. So where do you aim for?

It’s a trick question. The answer is neither and I can explain why thanks to Jeff Bezos.

The Scout Mindset

The traditional fake-it-until-you-make-it advice is you should err on the side of being overly confident. As Julia Galef says in The Scout Mindset:

Confidence is magnetic. It invites people to listen to you, follow you, and trust that you know what you’re doing. If you look up advice on how to be influential or persuasive, you’ll find lots of exhortations to believe in yourself.

But, if you look closely at how we use the word, confidence hides two different concepts behind a single word.

One is social confidence. This is also known as self-assurance. One model for self-assuredness is Jeff Bezos. When asked why they invested in Amazon in the early days, VC John Doer said (as recounted in ScoutMindset) :

I walked into the door and this guy with a boisterous laugh who was just exuding energy comes bounding down the steps. In that moment, I wanted to be in business with Jeff.

Alex above lacked social confidence and Amy, like Jeff Bezos, had plenty of it. And studies have shown that self-assuredness helps you succeed in life.

Epistemic Confidence

The second type of confidence is epistemic confidence. Epistemic confidence is a measure of how confident you are in an outcome. If I ask you to predict tomorrows lottery ticket number you can come up with a number, but you will have low confidence in it being correct.

Epistemic confidence is about uncertainty. If you have an opinion but you have low confidence in it you might preface it with “I’m unsure but” or “it appears to me” or “I think.”

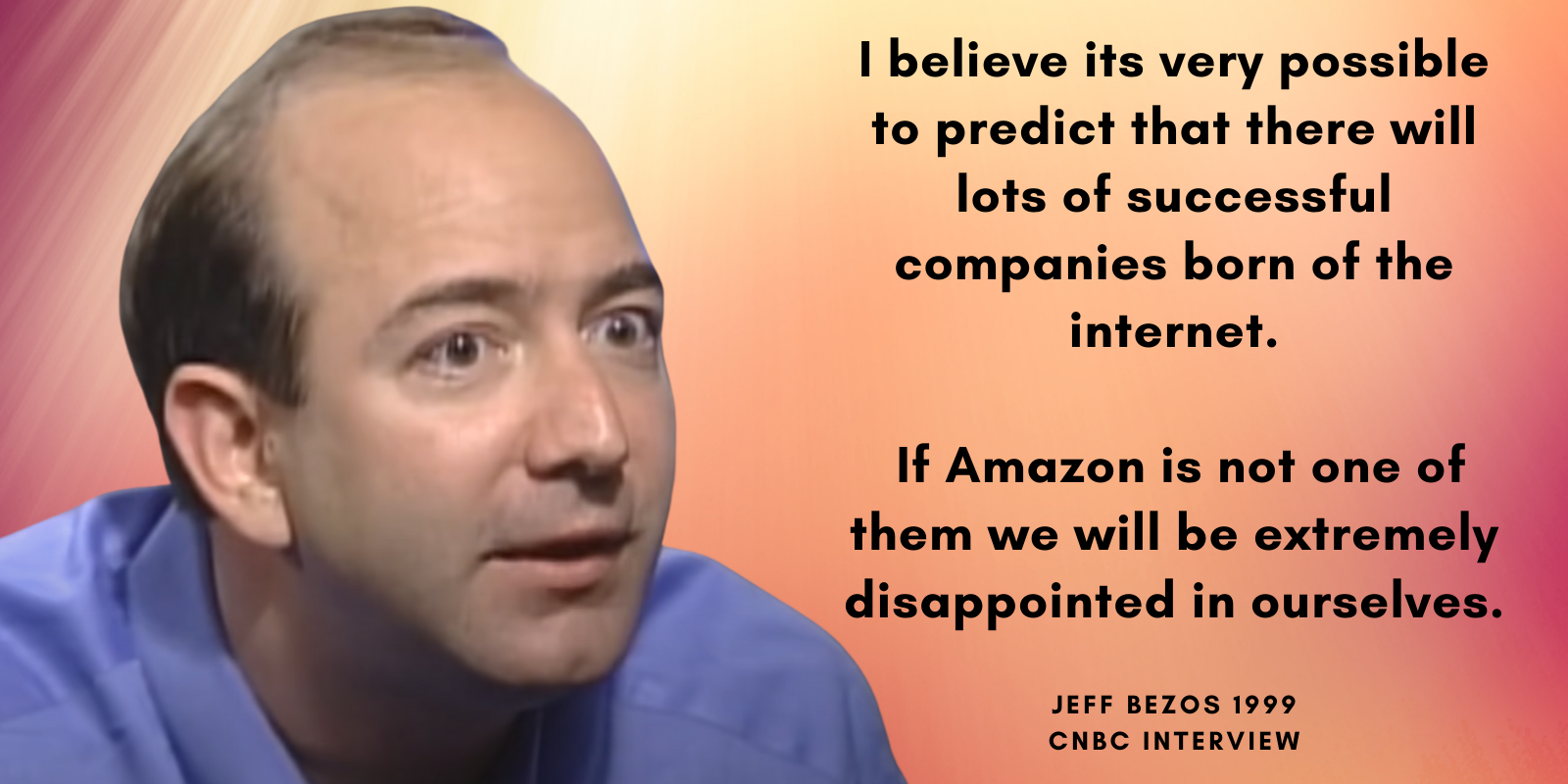

A great model of dealing with epistemic confidence is, again, Jeff Bezos. Here he is talking about his confidence in the success of Amazon in 1999 on CNBC:

Speaking to CNBC, as a CEO of a public company, is speaking to your investors. I would want to tell investors that Amazon would change the world but that is not how Bezos communicates:

![“It’s very hard to predict [who the winners will be]. There are no guarantees.” Jeff Bezos Quote](/blog/assets/images/confidently-uncertain/7650.png)

The whole interview is fascinating. Bezos never fails to communicate that the odds are long, but that he thinks Amazon’s a good bet anyway.

So copy Jeff Bezos. You want to be socially confident - confident in yourself, confident in who you are - but you want to be appropriately uncertain about the world. So don’t kid yourself into thinking your code is bug free when you have historical evidence to the contrary. It shouldn’t hurt your ego to acknowledge uncertainty.

As Scout Mindset says:

When people claim that “admitting uncertainty” makes you look bad, they’re invariably conflating these two very different kinds of uncertainty: uncertainty “in you,” caused by your own ignorance or lack of experience, and uncertainty “in the world,” caused by the fact that reality is messy and unpredictable.

How To Be Uncertain

Balancing these two related types of confidence can be a bit tricky. Scout Mindset offers some tips.

Never Say “I Don’t Know.”

Imagine you’re a software developer working on a service, and someone asks you why it’s down in a certain region of AWS. A perfectly correct answer is “I don’t know.” The problem is that “I don’t know” implies that the uncertainty is in you. It’s YOU who doesn’t know.

Instead of “I don’t know,” you should confidently explain the uncertainty: “I rolled out a change to that service yesterday, so it could be that, but until someone looks at logs it will be hard to know for sure.” You are now communicating not just that you are uncertain but also why you’re justified in being so.

You can even give estimates on the uncertainty: “nine times out of ten when something is wrong in just one region a re-deploy will fix the issue.”

Have a Plan

After you communicate that it’s reasonable to be uncertain, you want to share that you have a plan to minimize or address the uncertainty. Jeff Bezos had a plan for overcoming the unpredictability of the dot com boom: “I believe that if you can focus obsessively enough on customer experience, selection, ease of use, low prices… I think you have a good chance.”

This second step is what allows you to be socially confident in the face of the unknown: You have a plan. Jeff didn’t just say he was uncertain whether Amazon would succeed. He said that and then immediately followed with how he thought he could overcome the odds.

In other words, share that the uncertainty is out there in that world, and that you have a plan to overcome it. And having a plan can be as simple as saying, “Let me look into that”.

Let Me Look Into That

So that is how you can be confidently uncertain: Explain why things are uncertain and communicate that you have a plan.

This brings me back to Alex and Amy: if I could go back in time, I would tell them that instead of saying “Oh God, why did my task fail again” or “How can you fail it when you don’t know the requirements” they should have just said, “Let me look into that.” I’d also bring them each a copy of The Scout Mindset - That’s where I got this idea from.

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.

I’ve changed Alex and Amy’s names but, yeah, you probably know who you are. Hopefully you’ll forgive me for the characterization. You are both solid developers and we should catch up.↩︎