Concurrency in Go

We’re Earthly. We make building software simpler and therefore faster using containerization. Love Go’s concurrency model? Check out Earthly for managing your builds efficiently. Check us out.

Introduction

By default, computer programs are executed sequentially, usually line-by-line. Although this is very efficient, you may need to run multiple processes simultaneously or control the flow and runtime of your programs for numerous reasons. Luckily, Go gives us a way to run various processes concurrently or in parallel. Concurrency comes in handy for speed, process synchronization, and resource utilization.

What Is Concurrency?

“Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once. Parallelism is about doing lots of things at once.” — Rob Pike

Concurrency is the ability to run different program parts interchangeably, possibly using the same CPU core. Concurrent programs run various parts of a program individually on the same processor core.

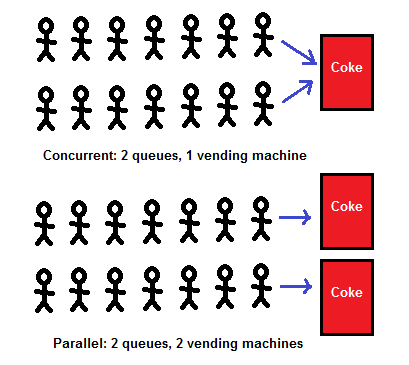

This is different from parallelism or parallel processing, which is the ability to run different parts of a program simultaneously on other CPU cores such that each core runs a process. Alvin Alexander illustrates the difference with an image of people waiting in line to use a vending machine.

Photo Credit: https://alvinalexander.com/photos/parallelism-vs-concurrency-programming/

One of the major selling points of the Go programming language is its first-class support for concurrency using Goroutines for creating multiple processes and channels which allow different GoRoutines to share data and communicate.

What Are Goroutines

GoRoutines are light-weight execution threads integrated into Go’s runtime that run independently, along with the initialized functions. Threads are the smallest sequential unit of a program’s execution within processes. Every process contains multiple threads.

Unlike regular operating system threads, Go’s runtime manages Goroutines independent of the machines hardware, and the Kernel manages OS threads by utilizing the computer’s hardware.

How to Use Goroutines

First, let’s write a couple functions without using a Goroutine.

func starter() {

fmt.Println("This is the starter on call")

}

func follow() {

fmt.Println("This is the follower on call")

}

func main(){

starter()

follow()

}The starter and follow functions print out strings in the order they are called in the main function.

This is the starter on call

This is the follower on callThis works just as we expected. The code in main() executed sequentially, the starter first, and then the follower.

Now let’s add a Goroutine, and see how it changes the behavior. Creating a goroutine is easy, you just prepend the function call with the go keyword.

func main() {

go starter()

follow()

}In the main function, the starter function has the go keyword prepended to create a Goroutine. Run this and you’ll get the following output.

This is the follower on callThis time when we run the main function, only the follow function prints out the string as shown above. This brings up a key lesson we need to understand when it comes to goroutines, which is go will not wait for go routines to finish. At least, not if we don’t write some code to tell it to.

So, what is happening in this function call is that the starter function gets spun off into its own goroutine, which means the main function doesn’t need to wait for starter to return anything. So it moves right on to the follow function. The follow function quickly runs and returns. The main function says, “Well that’s it, there is no more code for me to execute.” Go sees that the main function is done and it exits the program, all before starter gets a chance to do anything off in it’s own goroutine.

We can remedy this by having the program wait a couple of seconds to give the starter goroutine time to finish. If you’re following along, be sure to import the time package.

func main() {

go starter()

follow()

time.Sleep(time.Second + 2)

}Run this and we should get both print statements.

This is the follower on call

This is the starter on callSetting the program to sleep for two seconds is enough time to wait for the starter Goroutine to execute before the program exits. One problem you may have notices, now are follower is executing before our starter.

When you create a Goroutine, the execution time is unknown, and you’ll need your code to execute successfully before the program exits. Using a sleep timer isn’t great here because what if our goroutine takes more than 2 seconds to? Or less and we are waiting longer than we need to?

WaitGroups

WaitGroups are one way to ensure that a goroutine is completed before the program exits. WaitGroups are part of the sync package in Go’s standard library, so you’ll have to import the sync package.

import (

"Sync"

"fmt"

)To use wait groups, the function has to implement the WaitGroup type.

func starter(wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

fmt.Println("This is the starter on call")

defer wg.Done()

}

func follow() {

fmt.Println("This is the follower on call")

}The starter function implements the WaitGroup. On calling the function, when the starter function is done, the Done method will notify the WaitGroup, and the program can exit the process.

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(1)

go starter(&wg)

follow()

wg.Wait()

}In the main function where the starter function will be called, you will have to create a WaitGroup variable. Using the Add function of the WaitGroup, you can add a counter for the Goroutine; when the Goroutine runs, the counter decrements. The output is shown below:

This is the follower on call

This is the starter on callThe Wait method ensures that all Goroutines in the WaitGroup run before the main function exits. Also, you can use a Waitgroup with more than one goroutine.

Communicating Between Goroutines Using Channels

Your concurrent program may require communication between goroutines. Go provides functionality for bi-directional communication between goroutines in Channels. You can create a channel using the built-in make function. To create a channel, you’ll have to pass in the chan keyword and the data type you want use to communicate over the channel.

channels := make(chan string)To send a value through a channel, you’ll have to use the channel operator <- with the value on the right and the variable name on the left.

Here’s an example of passing data from a goroutine to a function using a channel.

func starter(ch chan string) {

fmt.Println("This is the starter on call")

ch <- "Hello,"

}

func follow(starter string) {

fmt.Println(starter, "From the starter function, \

This is the follower on call")

}The starter function takes in a string and sends the string to the ch channel after printing the string in the Println method. The follow function takes in a string and prints the string.

func main() {

channels := make(chan string) // unbuffered channel

defer close(channels)

go starter(channels) // takes in the channel and passes the string

receiver := <- channels // receiver takes the value in the channel

follow(receiver)

}In the main function, the channels variable is an empty channel, and the defer statement closes the channel once the communication is over. The starter goroutine takes in the channel, and the receiver variable receives the string from the channel passed into the follow function as the string argument it accepts. The follow function can run successfully as intended.

This is the starter on call

From the starter function, This is the follower on callChannels are not buffered on default, and sending and receiving are blocking operations. Goroutines need to wait for the receiver. You can use a buffered channel to prevent deadlocks instead of waiting for a receiver.

Channel Buffering and Synchronization

Go provides functionality for channel buffering. To create a buffered channel, you’ll have to specify the buffer length as a second argument to the make function when declaring a channel.

channels := make(chan string, 2) // buffer capacity is 2When you specify a buffer capacity, you can send the number of messages into the channel at once until the buffer is filled without having deadlocks and the goroutine on the receiving end has received the data.

func starter(ch chan string) {

fmt.Println("This is the starter on call")

ch <- "Hello,"

ch <- "What's up"

}

func follow(starter, starter2 string) {

fmt.Println(starter, starter2, "From the starter function,\

This is the follower on call")

}The starter function sends two strings through the ch channel. The strings will be received in the main function and passed as arguments in the follow function.

func main() {

channels := make(chan string, 2) // buffered channel

defer close(channels)

go starter(channels)

reciever1 := <- channels

reciever2 := <- channels

follow(reciever1, reciever2)

}In the main function, you declared the channels variable with a buffer capacity of two strings. The starter function takes in the channel variable and passes the strings to it. Because the buffer capacity of the channels variable is 2, you can only send two values through the channel.

Channel Directions

In the starter function, the channel can either be a sender or a receiver because a channel direction wasn’t specified. You can specify channel directions that are function parameters to increase the type-safety of your program.

You can pass in the channel operator (<-) to specify the channel direction. <-chan specifies that the channel can only send, and chan<- specifies that the channel can only receive.

func starter(entry chan<- string, message string) {

entry <- message //receive only, so it receives the string

}

func follower(sender <-chan string, receiver chan<- string) {

message := <-sender // send only, so it sends to the variable

receiver <- message // receive only, so it receives from the variable

}The starter function takes in a receive-only channel and a string that’ll be passed to the channel.

The follower function takes in the sender argument (send-only) and a receiver argument (receive-only). In the body of the follower function, a message variable is declared, and the sender variable sends the channel to the message variable that sends the string channel to the receiver argument.

func main() {

send := make(chan string, 1)

receive := make(chan string, 1)

starter(send, "Successfully sent a message")

follower(send, receive)

fmt.Println(<-receive)

}The send and receive variables are unbuffered channels. The starter function takes in the send channel and sends a message through the channel. The follower takes the send channel (containing the message from the starter variable) and the receive channel. Finally, the string from the send channel is printed.

Example Usecase of a Concurrency in Programs

Imagine you were building a web application, and users must sign in with credentials and an OTP (you store the OTP on a Redis database set to expiry within 5 minutes) to access their accounts.

The steps for the program could be:

- Generate a cryptographically secure random value.

- Store the value on the Redis database.

- Issue the OTP after authenticating the user.

- Change the user’s login status to

true.

You can take a step-by-step approach where, after authenticating the user, you generate the value before storing it in the database and issuing the OTP.

An alternative would be taking the concurrency approach. You can create a goroutine for generating the OTP during the authentication process before saving the OTP to the database if the user’s credentials are correct. After authenticating the user with both OTP and login credentials, you’re tasked with setting the Login status and serving subsequent resources; another case where you can use Goroutines.

The effects of using concurrency may be negligible when you have a limited amount of users hitting your server; however, as more users use your server, running processes concurrently would increase the speed of your application.

Here’s an article by Tarun Kundhiya that goes over many situations and scenarios where implementing concurrency in applications is advantageous.

Conclusion

Go provides tools like Mutex and Cond from the sync package to aid in writing concurrent programs. While concurrent programming can introduce complexity and challenges, with correct implementation, it can boost speed and performance. Be mindful of its pros and cons as you continue your programming journey.

If our discussion about concurrency in Go has piqued your interest, you might want to explore Earthly. It’s a tool that can increase the parallelism of your CI/CD build.

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.