Compiling Containers - Dockerfiles, LLVM, and BuildKit

We’re Earthly. We simplify and speed up software build processes with containerization. Earthly can enhance the reliability of your CI/CD process. Check it out.

Introduction

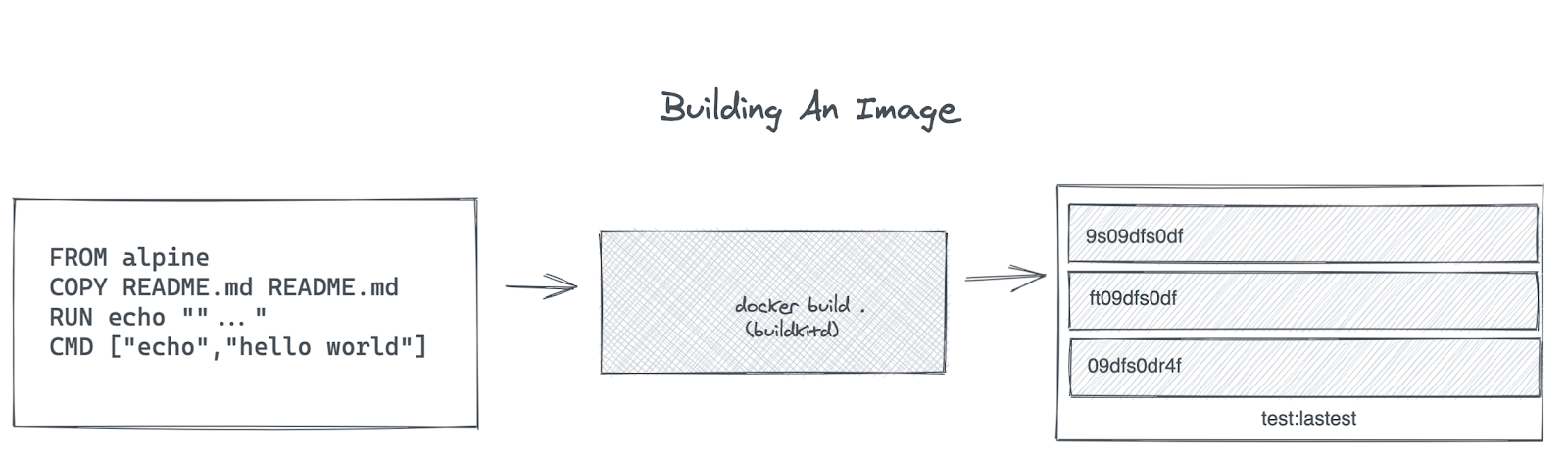

How are containers made? Usually, from a series of statements like RUN, FROM, and COPY, which are put into a Dockerfile and built. But how are those commands turned into a container image and then a running container? We can build up an intuition for how this works by understanding the phases involved and creating a container image ourselves. We will create an image programmatically and then develop a trivial syntactic frontend and use it to build an image.

On Docker Build

We can create container images in several ways. We can use Buildpacks, we can use build tools like Bazel or sbt, but by far, the most common way images are built is using docker build with a Dockerfile. The familiar base images Alpine, Ubuntu, and Debian are all created this way.

Here is an example Dockerfile:

FROM alpine

COPY README.md README.md

RUN echo "standard docker build" > /built.txt"We will be using variations on this Dockerfile throughout this tutorial.

We can build it like this:

> docker build . -t testBut what is happening when you call docker build? To understand that, we will need a little background.

Background

A docker image is made up of layers. Those layers form an immutable filesystem. A container image also has some descriptive data, such as the start-up command, the ports to expose, and volumes to mount. When you docker run an image, it starts up inside a container runtime.

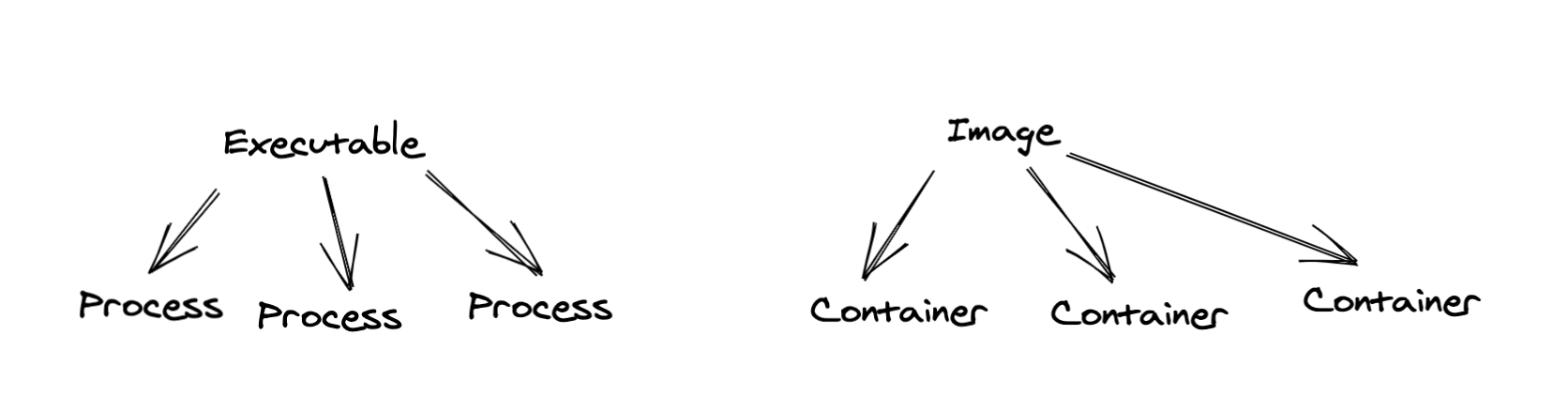

I like to think about images and containers by analogy. If an image is like an executable, then a container is like a process. You can run multiple containers from one image, and a running image isn’t an image at all but a container.

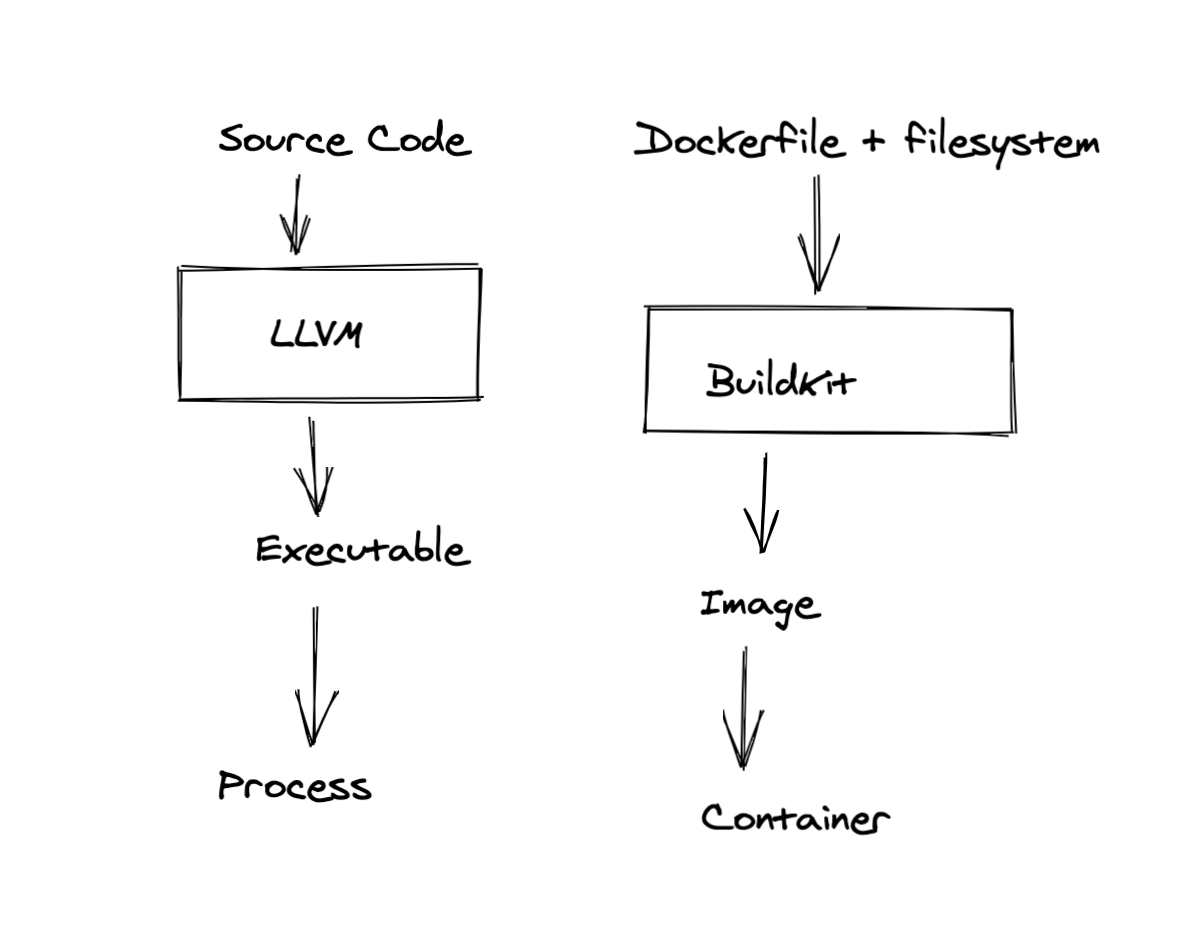

Continuing our analogy, BuildKit is a compiler, just like LLVM. But whereas a compiler takes source code and libraries and produces an executable, BuildKit takes a Dockerfile and a file path and creates a container image.

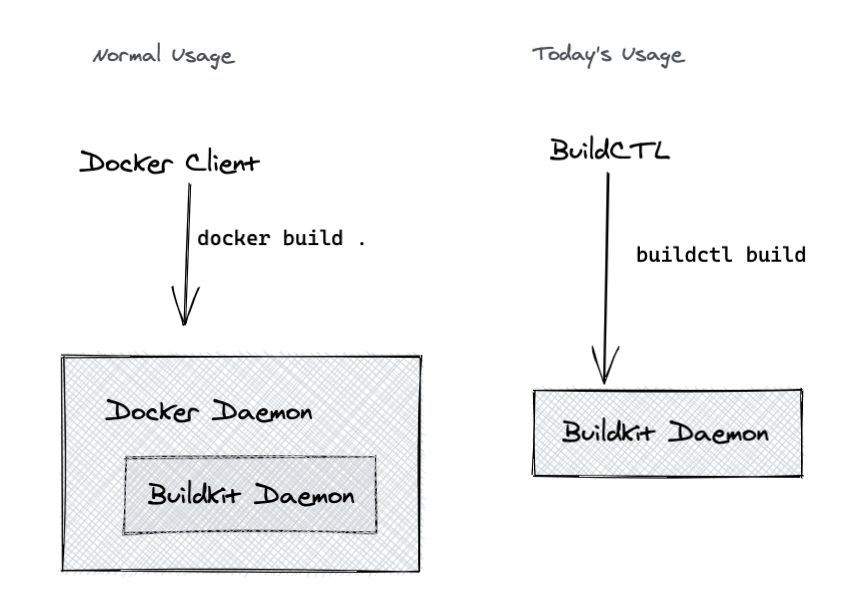

Docker build uses BuildKit, to turn a Dockerfile into a docker image, OCI image, or another image format. In this walk-through, we will primarily use BuildKit directly.

This primer on using BuildKit supplies some helpful background on using BuildKit, buildkitd, and buildctl via the command-line. However, the only prerequisite for today is running brew install buildkit or the appropriate OS equivalent steps.

How Do Compilers Work?

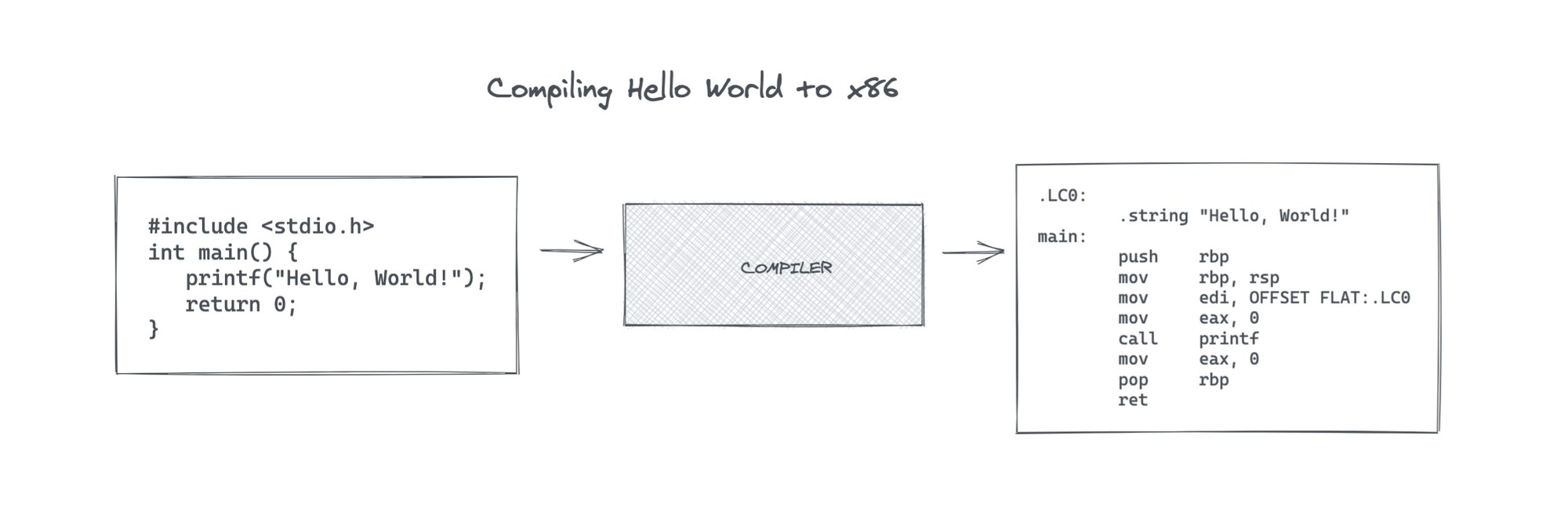

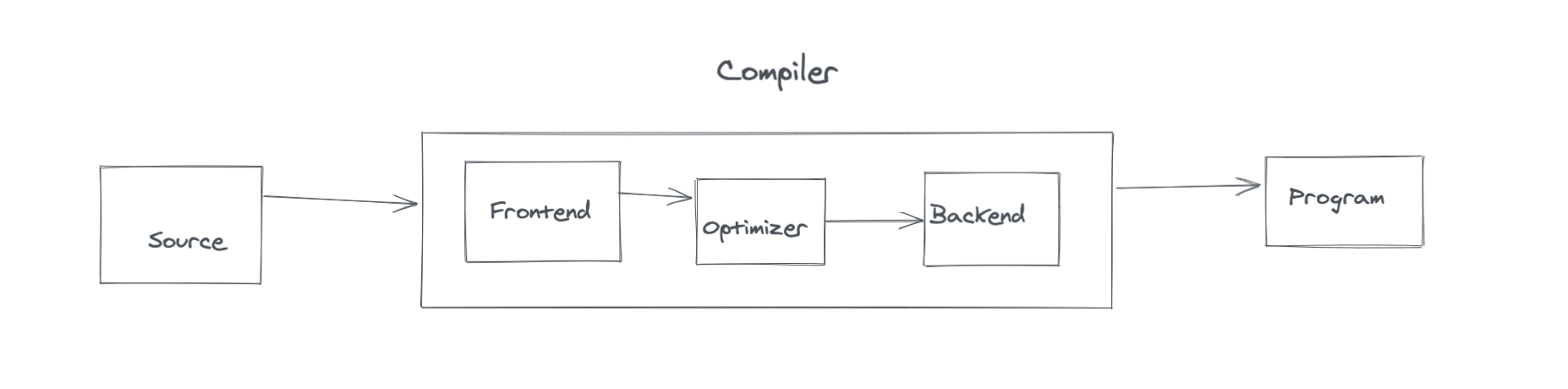

A traditional compiler takes code in a high-level language and lowers it to a lower-level language. In most conventional ahead-of-time compilers, the final target is machine code. Machine code is a low-level programming language that your CPU understands1.

Fun Fact: Machine Code VS. Assembly

Machine code is written in binary. This makes it hard for a human to understand. Assembly code is a plain-text representation of machine code that is designed to be somewhat human-readable. There is generally a 1-1 mapping between instructions the machine understands (in machine code) and the OpCodes in Assembly

Compiling the classic c “Hello, World” into x86 assembly code using the CLANG frontend for LLVM looks like this:

Creating an image from a dockerfile works a similar way:

BuildKit is passed the Dockerfile and the build context, which is the present working directory in the above diagram. In simplified terms, each line in the dockerfile is turned into a layer in the resulting image. One significant way image building differs from compiling is this build context. A compiler’s input is limited to source code, whereas docker build takes a reference to the host filesystem as an input and uses it to perform actions such as COPY.

There Is a Catch

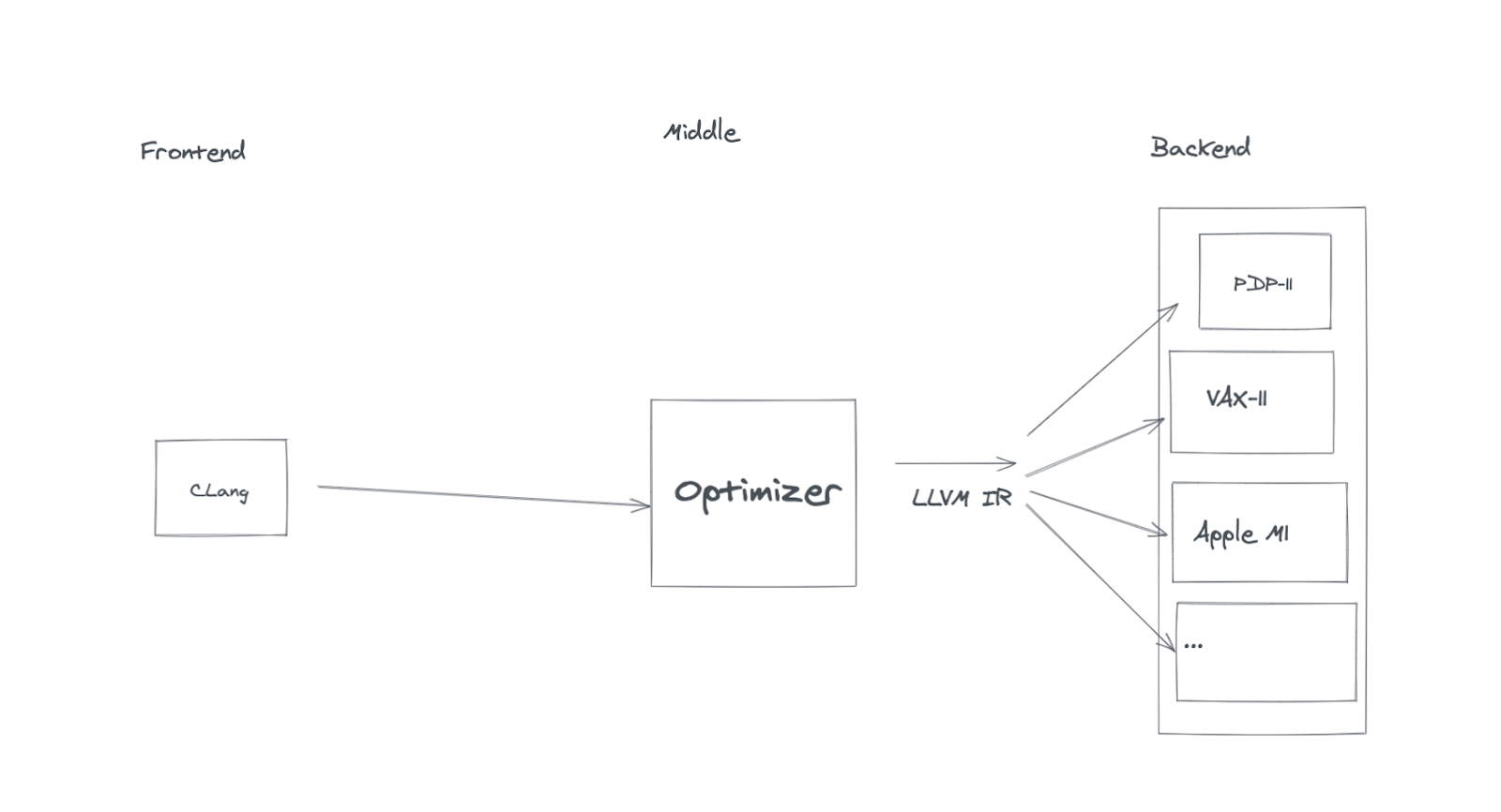

The earlier diagram of compiling “Hello, World” in a single step missed a vital detail. Computer hardware is not a singular thing. If every compiler were a hand-coded mapping from a high-level language to x86 machine code, then moving to the Apple M1 processor would be quite challenging because it has a different instruction set.

Compiler authors have overcome this challenge by splitting compilation into phases. The traditional phases are the frontend, the backend, and the middle. The middle phase is sometimes called the optimizer, and it deals primarily with an internal representation (IR).

This staged approach means you don’t need a new compiler for each new machine architecture. Instead, you just need a new backend. Here is an example of what that looks like in LLVM:

Intermediate Representations

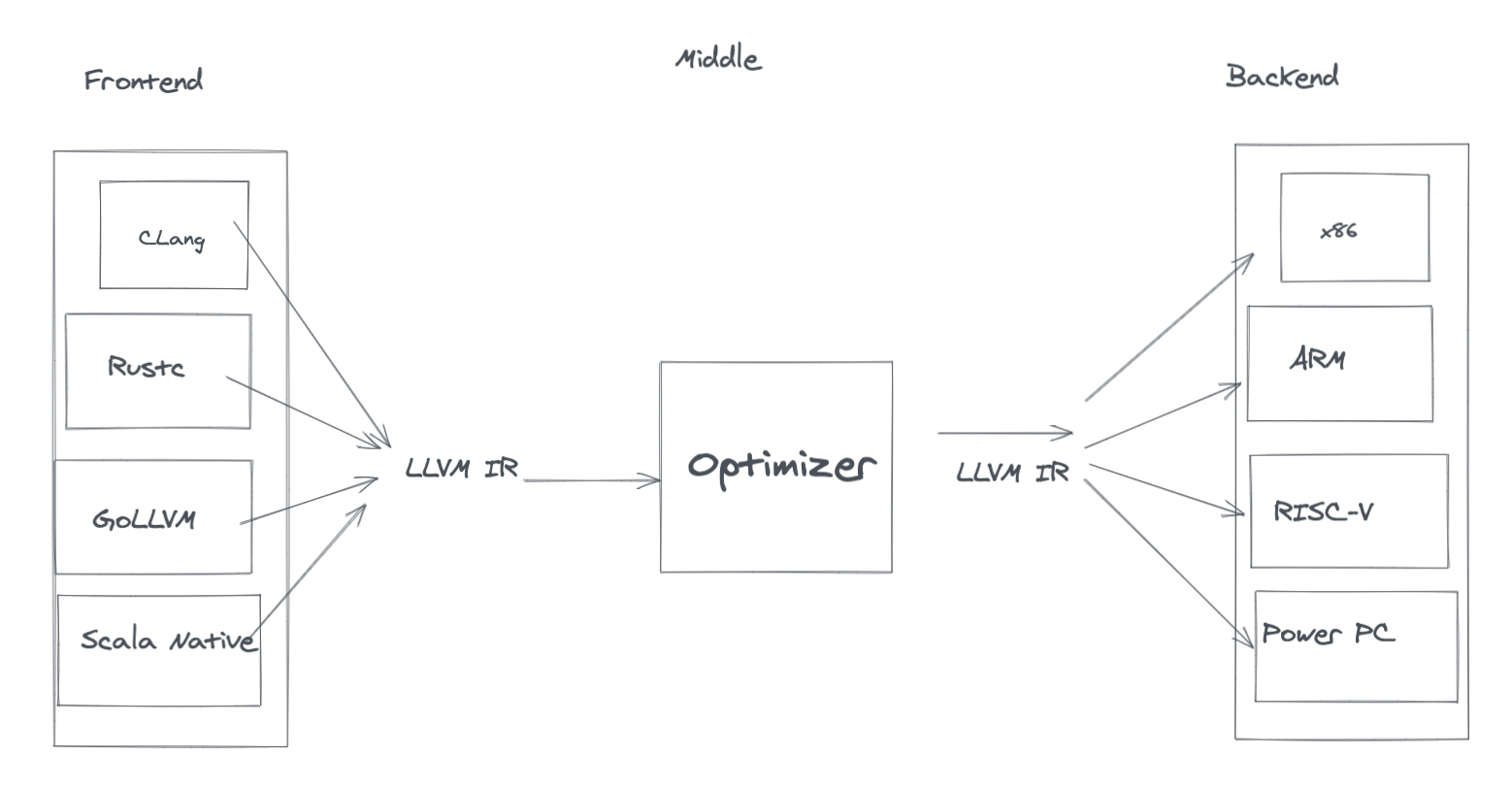

This multiple backend approach allows LLVM to target ARM, X86, and many other machine architectures using LLVM Intermediate Representation (IR) as a standard protocol. LLVM IR is a human-readable programming language that backends need to be able to take as input. To create a new backend, you need to write a translator from LLVM IR to your target machine code. That translation is the primary job of each backend.

Once you have this IR, you have a protocol that various phases of the compiler can use as an interface, and you can build not just many backends but many frontends as well. LLVM has frontends for numerous languages, including C++, Julia, Objective-C, Rust, and Swift.

If you can write a translation from your language to LLVM IR, LLVM can translate that IR into machine code for all the backends it supports. This translation function is the primary job of a compiler frontend.

In practice, there is much more to it than that. Frontends need to tokenize and parse input files, and they need to return pleasant errors. Backends often have target-specific optimizations to perform and heuristics to apply. But for this tutorial, the critical point is that having a standard representation ends up being a bridge that connects many front ends with many backends. This shared interface removes the need to create a compiler for every combination of language and machine architecture. It is a simple but very empowering trick!

BuidKit

Images, unlike executables, have their own isolated filesystem. Nevertheless, the task of building an image looks very similar to compiling an executable. They can have varying syntax (dockerfile1.0, dockerfile1.2), and the result must target several machine architectures (arm64 vs. x86_64).

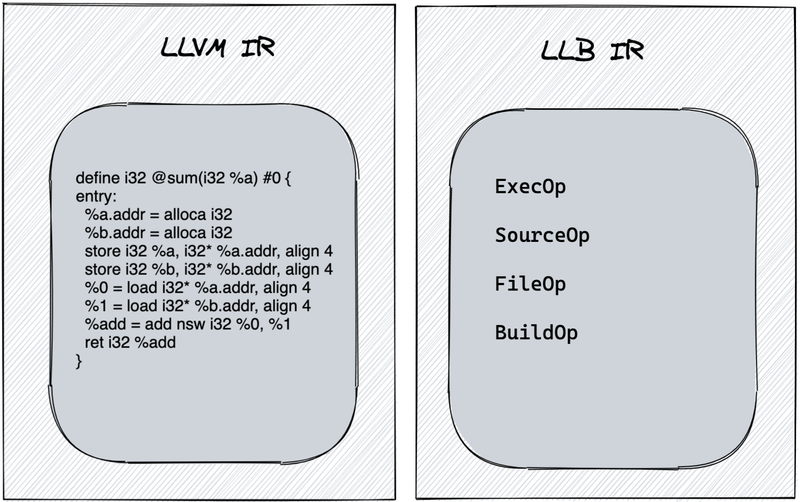

“LLB is to Dockerfile what LLVM IR is to C” - BuildKit Readme

This similarity was not lost on the BuildKit creators. BuildKit has its own intermediate representation, LLB. And where LLVM IR has things like function calls and garbage-collection strategies, LLB has mounting filesystems and executing statements.

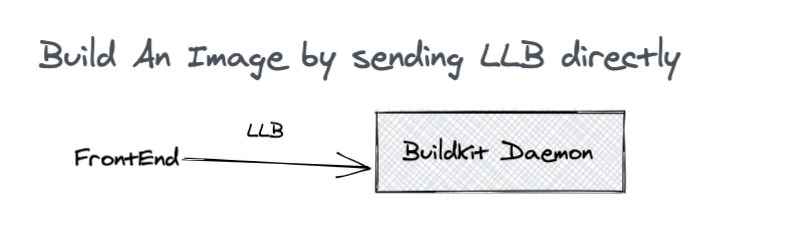

LLB is defined as a protocol buffer, and this means that BuildKit frontends can make GRPC requests against buildkitd to build a container directly.

Programmatically Making a Image

Alright, enough background. Let’s programmatically generate the LLB for an image and then build an image.Using Go

In this example, we will be using Go which lets us leverage existing BuildKit libraries, but it’s possible to accomplish this in any language with Protocol Buffer support.

Import LLB definitions:

import (

"github.com/moby/buildkit/client/llb"

)Create LLB for an Alpine image:

func createLLBState() llb.State {

return llb.Image("docker.io/library/alpine").

File(llb.Copy(llb.Local("context"), "README.md", "README.md")).

Run(llb.Args([]string{"/bin/sh", "-c", "echo \"programmatically built\" > ↩

\ built.txt"})).Root()

}We are accomplishing the equivalent of a FROM by using llb.Image. Then, we copy a file from the local file system into the image using File and Copy. Finally, we RUN a command to echo some text to a file. LLB has many more operations, but you can recreate many standard images with these three building blocks.

The final thing we need to do is turn this into protocol-buffer and emit it to standard out:

func main() {

dt, err := createLLBState().Marshal(context.TODO(), llb.LinuxAmd64)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

llb.WriteTo(dt, os.Stdout)

}Let’s look at the what this generates using the dump-llb option of buildctl:

go run ./writellb/writellb.go | \

buildctl debug dump-llb | \

jq .We get this JSON formatted LLB:

{

"Op": {

"Op": {

"source": {

"identifier": "local://context",

"attrs": {

"local.unique": "s43w96rwjsm9tf1zlxvn6nezg"

}

}

},

"constraints": {}

},

"Digest": "sha256:c3ca71edeaa161bafed7f3dbdeeab9a5ab34587f569fd71c0a89b4d1e40d77f6",

"OpMetadata": {

"caps": {

"source.local": true,

"source.local.unique": true

}

}

}

{

"Op": {

"Op": {

"source": {

"identifier": "docker-image://docker.io/library/alpine:latest"

}

},

"platform": {

"Architecture": "amd64",

"OS": "linux"

},

"constraints": {}

},

"Digest": "sha256:665ba8b2cdc0cb0200e2a42a6b3c0f8f684089f4cd1b81494fbb9805879120f7",

"OpMetadata": {

"caps": {

"source.image": true

}

}

}

{

"Op": {

"inputs": [

{

"digest": "sha256:665ba8b2cdc0cb0200e2a42a6b3c0f8f684089f4cd1b81494fbb9805879120f7",

"index": 0

},

{

"digest": "sha256:c3ca71edeaa161bafed7f3dbdeeab9a5ab34587f569fd71c0a89b4d1e40d77f6",

"index": 0

}

],

"Op": {

"file": {

"actions": [

{

"input": 0,

"secondaryInput": 1,

"output": 0,

"Action": {

"copy": {

"src": "/README.md",

"dest": "/README.md",

"mode": -1,

"timestamp": -1

}

}

}

]

}

},

"platform": {

"Architecture": "amd64",

"OS": "linux"

},

"constraints": {}

},

"Digest": "sha256:ba425dda86f06cf10ee66d85beda9d500adcce2336b047e072c1f0d403334cf6",

"OpMetadata": {

"caps": {

"file.base": true

}

}

}

{

"Op": {

"inputs": [

{

"digest": "sha256:ba425dda86f06cf10ee66d85beda9d500adcce2336b047e072c1f0d403334cf6",

"index": 0

}

],

"Op": {

"exec": {

"meta": {

"args": [

"/bin/sh",

"-c",

"echo \"programmatically built\" > /built.txt"

],

"cwd": "/"

},

"mounts": [

{

"input": 0,

"dest": "/",

"output": 0

}

]

}

},

"platform": {

"Architecture": "amd64",

"OS": "linux"

},

"constraints": {}

},

"Digest": "sha256:d2d18486652288fdb3516460bd6d1c2a90103d93d507a9b63ddd4a846a0fca2b",

"OpMetadata": {

"caps": {

"exec.meta.base": true,

"exec.mount.bind": true

}

}

}

{

"Op": {

"inputs": [

{

"digest": "sha256:d2d18486652288fdb3516460bd6d1c2a90103d93d507a9b63ddd4a846a0fca2b",

"index": 0

}

],

"Op": null

},

"Digest": "sha256:fda9d405d3c557e2bd79413628a435da0000e75b9305e52789dd71001a91c704",

"OpMetadata": {

"caps": {

"constraints": true,

"platform": true

}

}

}Looking through the output, we can see how our code maps to LLB.

Here is our Copy as part of a FileOp:

"Action": {

"copy": {

"src": "/README.md",

"dest": "/README.md",

"mode": -1,

"timestamp": -1

}Here is mapping our build context for use in our COPY command:

"Op": {

"source": {

"identifier": "local://context",

"attrs": {

"local.unique": "s43w96rwjsm9tf1zlxvn6nezg"

}

}Similarly, the output contains LLB that corresponds to our RUN and FROM commands.

Building Our LLB

To build our image, we must first start buildkitd:

> docker run --rm --privileged -d --name buildkit moby/buildkit

> export BUILDKIT_HOST=docker-container://buildkitWe can then build our image like this:

> go run ./writellb/writellb.go | \

buildctl build \

--local context=. \

--output type=image,name=docker.io/agbell/test,push=trueThe output flag lets us specify what backend we want BuildKit to use. We will ask it to build an OCI image and push it to docker.io.

Real-World Usage

In the real-world tool, we might want to programmatically make sure buildkitd is running and send the RPC request directly to it, as well as provide friendly error messages. For tutorial purposes, we will skip all that.

We can run it like this:

> docker run -it --pull always agbell/test:latest /bin/shAnd we can then see the results of our programmatic COPY and RUN commands:

> cat built.txt

programmatically built

> ls README.md

README.mdThere we go! The full code example can be a great starting place for your own programmatic docker image building.

A True Frontend for BuildKit

A true compiler front end does more than just emit hard coded IR. A proper frontend takes in files, tokenizes them, parses them, generates a syntax tree, and then lowers that syntax tree into the internal representation. Mockerfiles are an example of such a frontend:

#syntax=r2d4/mocker

apiVersion: v1alpha1

images:

- name: demo

from: ubuntu:16.04

package:

install:

- curl

- git

- gccAnd because Docker build supports the #syntax command we can even build a Mockerfiles directly with docker build.

> docker build -f mockerfile.yamlTo support the #syntax command, all that is needed is to put the frontend in a docker image that accepts a GRPC request in the correct format, publish that image somewhere. At that point, anyone can use your frontend docker build by just using #syntax=yourimagename.

Building Our Own Example Frontend for Docker build

Building a tokenizer and a parser as a GRPC service is beyond the scope of this article. But we can get our feet wet by extracting and modifying an existing frontend. The standard dockerfile frontend is easy to disentangle from the Moby project. I’ve pulled the relevant parts out into a stand-alone repository. Let’s make some trivial modifications to it and test it out.

So far, we’ve only used the docker commands FROM, RUN and COPY. At a surface level, with its capitalized commands, Dockerfile syntax looks a lot like the programming language INTERCAL. Let change these commands to their INTERCAL equivalent and develop our own Ickfile format 2.

| Dockerfile | Ickfile |

|---|---|

| FROM | COME FROM |

| RUN | PLEASE |

| COPY | STASH |

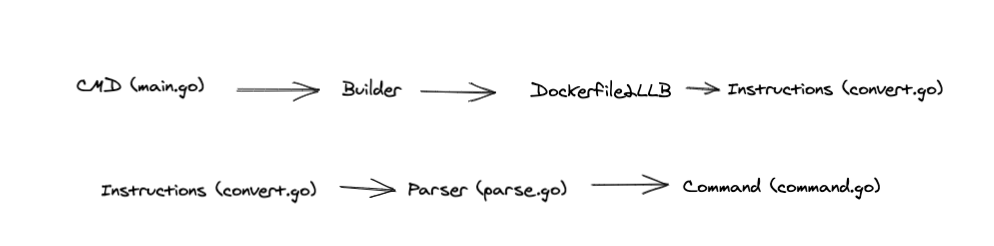

The modules in the dockerfile frontend split the parsing of the input file into several discreet steps, with execution flowing this way:

For this tutorial, we are only going to make trivial changes to the frontend. We will leave all the stages intact and focus on customizing the existing commands to our tastes. To do this, all we need to do is change command.go:

package command

// Define constants for the command strings

const (

Copy = "stash"

Run = "please"

From = "come_from"

...

)Then we build our image:

> docker build . -t agbell/ickAnd we can use this image as a BuildKit frontend and build images with it like this:

#syntax=agbell/ick

COME_FROM alpine

STASH README.md README.md

PLEASE echo "custom frontend built" > /built.txt"> DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1 docker build . -f ./Ickfile -t ick And we can run it just like any other image:

> docker run -it ick /bin/shAnd we can then see results of our STASH and PLEASE commands:

> cat built.txt

custom frontend built

> ls README.md

README.mdI’ve pushed this image to Docker Hub. Anyone can start building images using our ickfile format by adding #syntax=agbell/ick to an existing Dockerfile. No manual installation is required!

Enabling BuildKit

BuildKit is included but not enabled by default in the current version of Docker (version 20.10.2). To instruct docker build to use BuildKit set the following environment variable DOCKER_BUILDKIT=1. This will not be necessary once BuildKit reaches general availability.

Conclusion

We have learned that a three-phased structure borrowed from compilers powers building images, that an intermediate representation called LLB is the key to that structure. Empowered by the knowledge, we have produced two frontends for building images.

This deep dive on frontends still leaves much to explore. If you want to learn more, I suggest looking into BuildKit workers. Workers do the actual building and are the secret behind docker buildx, and multi-archtecture builds. docker build also has support for remote workers and cache mounts, both of which can lead to faster builds.

Earthly uses BuildKit internally for its repeatable build syntax. Without it, our containerized Makefile-like syntax would not be possible. If you want a saner CI process, then you should check it out.

There is also much more to explore about how modern compilers work. Modern compilers often have many stages and more than one intermediate representation, and they are often able to do very sophisticated optimizations.3

The difference between the two is murky, but I like to think of a transpiler as something that translates from one human-readable text-based programming language to another. The java compiler translates Java code to java byte code, which is a binary format. Meanwhile, PureScript, which translates to JavaScript, is regarded as a transpiler because JavaScript is text-based.

Fun Fact: You may have heard the term transpiler or transcompiler in the past. Transpilers are compilers that transform one programming language into another. If all compilers translate from one language to another, then what makes something a transpiler?↩︎

Ick is the name of the INTERCAL compiler. Therefore Ickfile can be its Dockerfile equivalent.↩︎

If you want to learn more about optimizing compilers, Matt Godbolt’s article on C++ Optimizations is a great place to start. The book Building an Optimizing Compiler is also often recommended online.↩︎