Running Containers on AWS Lambda

We’re Earthly. We make building software simpler and therefore faster. This article covers running containers in AWS Lambda, which is a great approach to prevent vendor lock-in. If you’re interested in a simple and containerized approach to building software that prevents CI vendor lock in then check us out.

Most of the code I’ve had running on AWS’s cloud has been in docker containers, running in Kubernetes clusters. And from my perspective, AWS was invisible. All I needed to concern myself with was the intricacies of getting the YAML for kubectl apply right. Of course, the cluster’s configuration was not my concern unless something went wrong, but I could then ping some Ops expert to help me out. But all that seems overkill for many tasks – the operational burden of maintaining Kubernetes is not free.

What if I want a simple container running in my AWS account, with some endpoints open to the world? What is the best way to get that in place? AWS offers many options: Amazon Elastic Container Service (ECS), Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS), AWS App Runner, and AWS Lightsail. Maybe there are more options? I’m not sure how anyone keeps up with the myriad AWS possibilities. But, an option with some excellent attributes is AWS Lambda.

Containers on AWS Lambda

In its first revision, AWS Lambda supported giving the lambda a zip file of code, and that was about it. But it had two exciting scalability features. One, it could scale up to thousands of instances based on request load, and two, it scaled down to zero when no requests were coming in. That aggressive scheduling, combined with a billing structure where you only for the time your lambda is running, caused all the buzz around lambdas back when it was launched in 2014.

AWS Lambda is a compute service that runs your code in response to events and automatically manages the compute resources for you, making it easy to build applications that respond quickly to new information. AWS Lambda starts running your code within milliseconds of an event such as an image upload, in-app activity, website click, or output from a connected device. You can also use AWS Lambda to create new back-end services where compute resources are automatically triggered based on custom requests.

But, I never got interested in lambdas myself. I worked in Scala, which runs on the JVM, which has a slow start-up time, and I also was into containers as a packaging unit and so although I heard people talk about lambda’s I didn’t pay attention.

But then, in 2020, AWS added support for containers. This may be naive, but the lambda product suddenly made more sense to me. If I could take my app, wrap it up in a container, which I was doing already, and have it running in AWS Lambda, it was like getting to deploy things into a giant Kubernetes cluster in the sky. The horizontal scaling features that were hard to get right in Kubernetes (HPAScaleToZero), were built into lambdas, and if your app has a slow start up time, with provisioned concurrency, you can always keep some instances running, never scaling back right to zero.

All of this to say, 8 years after its launch, I’m starting to see what the hype is about. So let me show you the setup for running a container in a Lambda.

What I’m going to make will be pretty straightforward. It will be a small node.js app that will take a URL, download it, and return the results – basically a simple web proxy.

TypeScript Lambda

The first thing I’m going to do is create a TypeScript file that will be the bulk of my lambda. Any programming language that can run inside a container will work, though. The main trick is just conforming to the shape of input and output expected by a lambda.

For instance, when I make a request against the AWS API Gateway that I’ll be setting up shortly, like this:

curl ((URL))/endpoint/?url=https://earthly.dev/blog/golang-monorepo/Then AWS Lambda will receive the event like this:

{

"queryStringParameters": {

"url": "https://earthly.dev/blog/golang-monorepo/"

}

}And if I want to return a plain text 500 error from my lambda I need to return a JSON object like this:

{

"statusCode" : 500,

"headers" : {

"content-type": "text/plain; charset=utf-8"

},

"body" : "Some error fetching the content"

}With that in mind, my TypeScript code looks like this:

'use strict';

const axios = require("axios").default;

exports.handler = (event: { queryStringParameters: { url: string; }; }) => {

if (!event.queryStringParameters || !event.queryStringParameters.url) {

let response = {

statusCode: 200,

headers: {

"content-type": "text/plain; charset=utf-8"

},

body: "Please provide a url as a query string parameter"

};

return (Promise.resolve(response));

} else {

const url = event.queryStringParameters.url;

return call(url)

}

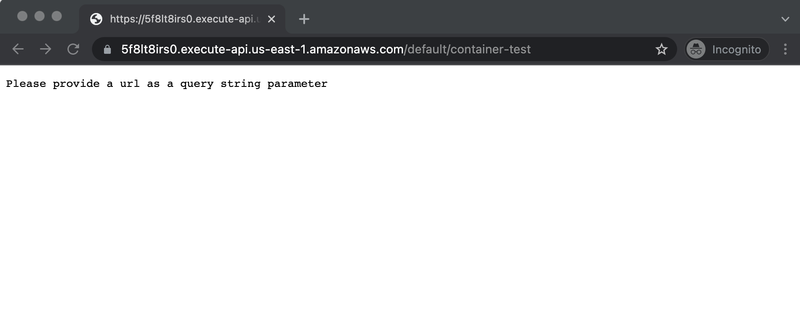

};I’m returning an explanatory message in plain text if the URL is missing, and otherwise, I return the result of call.

Since this is running in a container, call could call out to other programs installed in the container – perhaps downloading the html, and running an html minimizer? But for tutorial purposes, all it does is download the html content and return it as text.

function call(url: string) {

console.log("Getting:" + url);

return axios

.get(url)

.then((response: { data: string }) => {

console.log("Got content for:" + url );

return {

statusCode: 200,

headers: {

"content-type": "text/plain; charset=utf-8"

},

body: response

};

})

.catch((error: Error) => {

return {

statusCode: 500,

headers: {

"content-type": "text/plain; charset=utf-8"

},

body: "Some error fetching the content"

};

});

}I build this file with tsc into built/app.js, and then I wrap it up into a docker container for deployment to AWS Lambda.

FROM public.ecr.aws/lambda/nodejs:12

COPY package*.json ./

COPY built/*.js ./

RUN npm install

CMD [ "app.handler" ]I’m using Amazon’s suggested base container for Node.js which is a Red Hat linux container with the AWS lambda runtime installed.

Using Amazon’s images, the lambda runtime is already installed, and everything is configured for it to start up. I can see this using docker inspect

{

...

"Env": [

"LAMBDA_TASK_ROOT=/var/task",

"LAMBDA_RUNTIME_DIR=/var/runtime"

],

"WorkingDir": "/var/task",

"Entrypoint": [

"/lambda-entrypoint.sh"

],

...

}Amazon provides several container bases, but you can also install the container base of your choosing.

Now, let’s run something.

Testing Lambdas Locally

With the app containerized, it’s straightforward to test it locally:

First, I build it:

$ docker build i -t 733977735356.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/container-test .Then I can run it.

$ docker run -p 9000:8080 /

733977735356.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/container-test:latestAnd exercise it.

$ curl -XPOST "http://localhost:9000/2015-03-31/functions/function/invocations"

-d '{

"queryStringParameters": {

"url": "https://icanhazip.com/"

}

}'{

"statusCode":200,

"headers":

{

"content-type":"text/plain; charset=utf-8"

},

"body":"76.6.XXX.XXX\n"

}Note how I need to make my requests in the same fashion the API Gateway will. My actual API can be accessed via GET requests with a URL parameter, but to exercise it when no API Gateway sits in front of it, I need to simulate the lambda runtime by using a properly formatted POST.

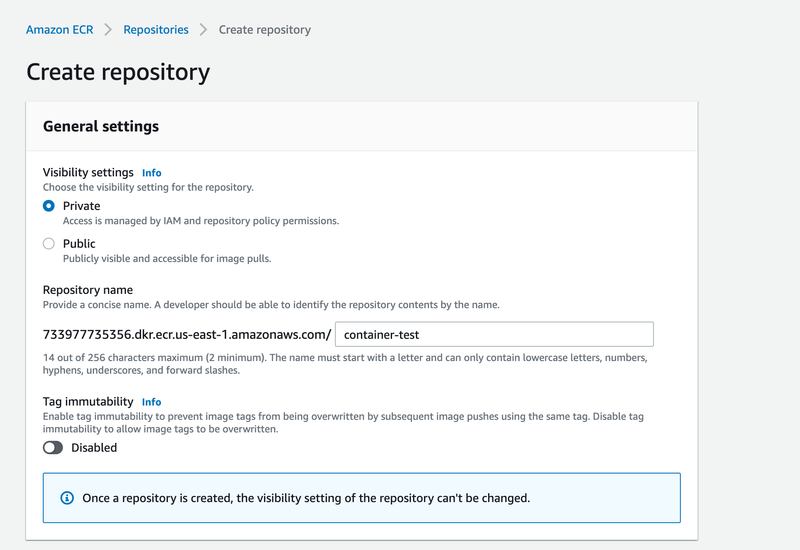

Elastic Container Registry

After that, I need to push my image to AWS ECR.

First I create a repository:

Then I log in and push to it.

$ aws ecr get-login-password --region us-east-1 | \

docker login --username AWS --password-stdin \

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com [733977735356.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/container-test]

6f55f8f6a022: Pushed

ff595bbcde74: Pushed

428b5d37bdb8: Pushed

aa262ea90a60: Pushed

b84abea626b7: Pushed

c51ba664b438: Pushed

2b9913d02f84: Pushed

d589926497ff: Pushed

00a4e675f0b7: Pushed

3f1bccf018a1: Pushed

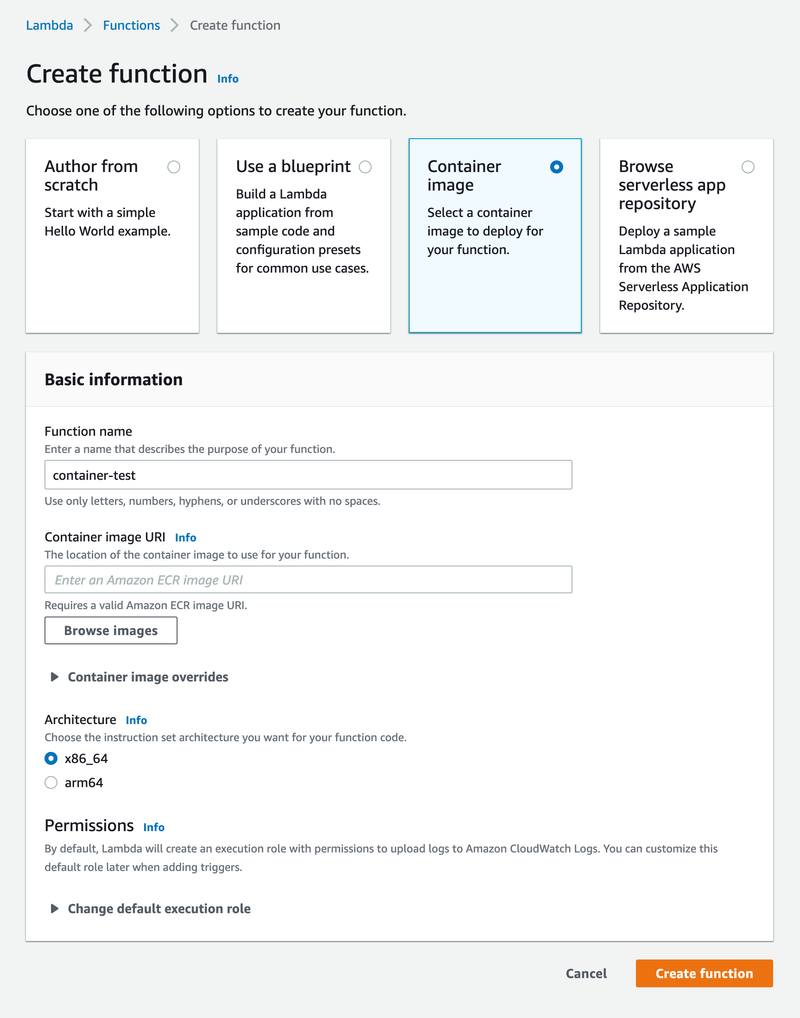

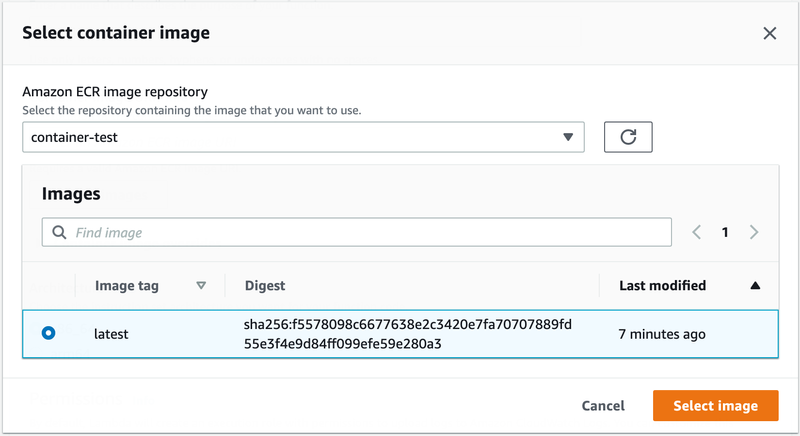

latest: digest: sha256:f5578098c6677638e2 size: 2420And then, create the lambda by selecting ‘Create Function’ and ‘Container Image’.

Then I select my image.

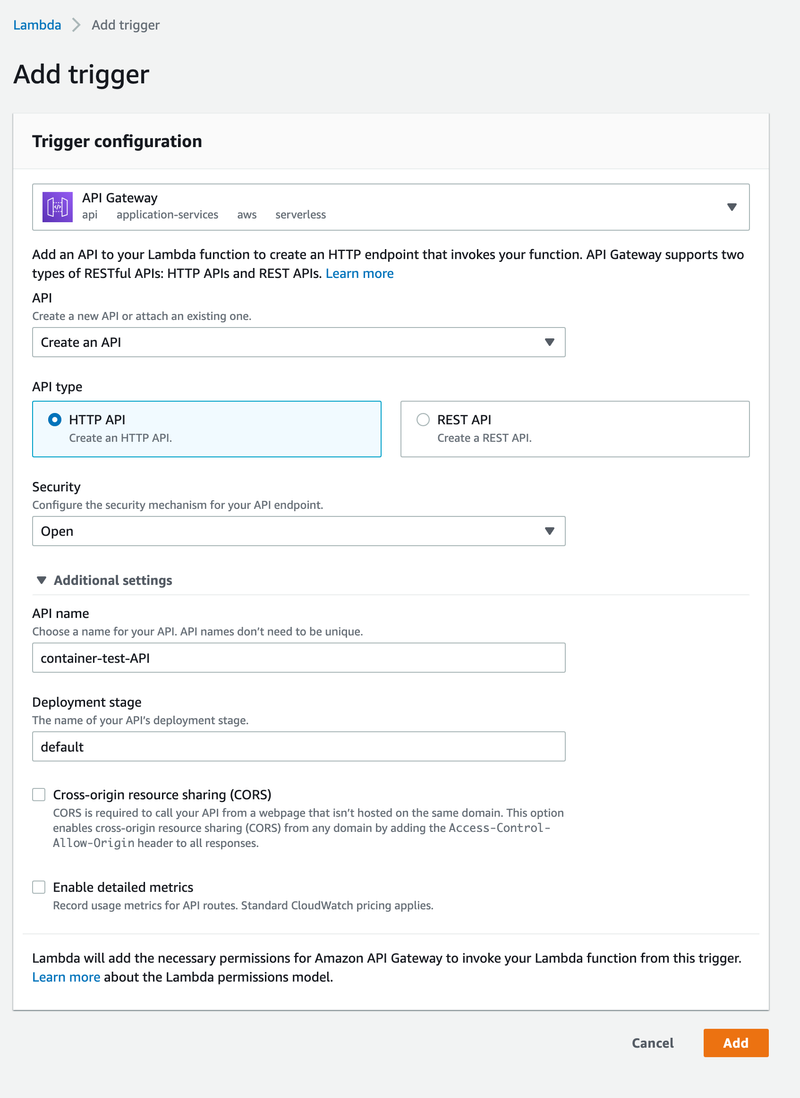

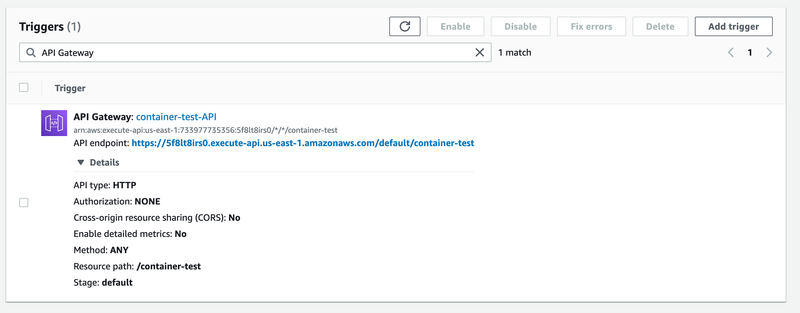

And then create a trigger.

At this point, I’m all set up, and I can start using my lambda.

Calling My Endpoint

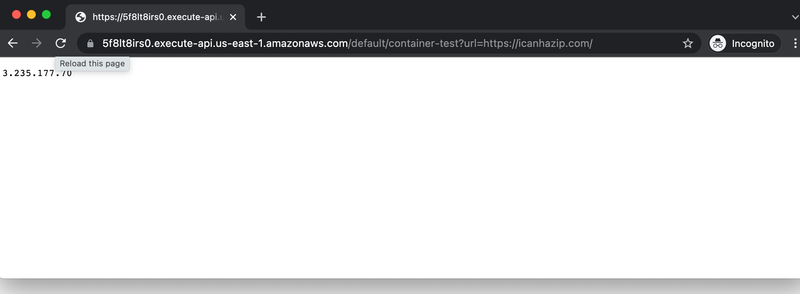

Amazon provides me with an URL and an endpoint, which I can call via my web browser.

It’s also simple to test it with a curl at the command line. The IP returned by requesting I can haz IP via this simple proxy is not my IP, but the IP Amazon is using to make the requests.

$ curl https://5f8lt8irs0.execute-api.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/default/container-test\?url\=https://icanhazip.com/

100.27.35.7Side Note: Home Path

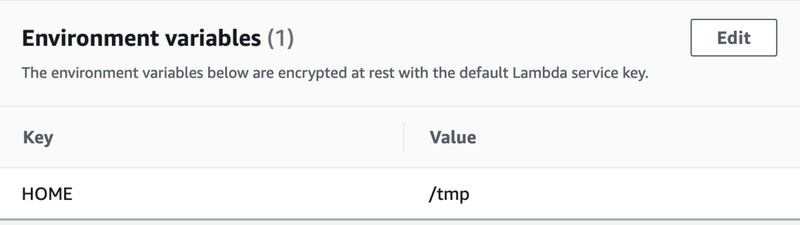

If you are spawning processes and running things in a shell inside your container, inside your lambda, be aware that the home directory, as of March, 2022 is not properly configured and you will get an error like this:

ENOENT: no such file or directory, mkdir '/home/sbx_user1051/See this error, but the easiest way to fix is just set $HOME to /tmp in the environmental variables section of lambda configuration.

Deploying Changes

One thing that caught me out with this solution is that, although I’ve deployed :latest, updating the latest image doesn’t change whats running in the lambda. Instead, the lambda just uses the tag to look up the sha of a container, pulls based on that sha, and runs that.

I can quickly deploy a new image using the aws cli, though.

aws lambda update-function-code \

--region us-east-1 \

--function-name container-test \

--image-uri 733977735356.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/container-test:latestSo there you go, I have containers working in lambdas. And this will work with any software stack that you can get inside a linux container.

Continuous Deployment

From where I’m at now, it’s not far to a full deployment solution.

To get there, first I’ll make my docker container inside an Earthfile.

FROM public.ecr.aws/lambda/nodejs:12

build:

COPY package*.json readme.txt ./

COPY built/*.js ./

RUN npm install

CMD [ "app.handler" ]

SAVE IMAGE 733977735356.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/container-test:latestThen, in the same Earthfile, I need a deploy step. First I use the aws cli image:

deploy:

FROM amazon/aws-cliThen I need to pass in AWS config and AWS credentials as secrets. I do this using a secret mount.

RUN --mount=type=secret,target=/root/.aws/config,id=+secrets/config \

--mount=type=secret,target=/root/.aws/credentials,id=+secrets/credentials \

--no-cache \This I deploy away, using aws lambda update-function-code. All together it looks like this:

deploy:

FROM amazon/aws-cli

RUN --mount=type=secret,target=/root/.aws/config,id=+secrets/config \

--mount=type=secret,target=/root/.aws/credentials,id=+secrets/credentials \

--no-cache \

aws lambda update-function-code \

--region us-east-1 \

--function-name text-mode \

--image-uri 733977735356.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/text-mode:latestThen in my chosen CI, when something is merged into my main branch, I just run earthly +build --push, and earthly +deploy, and my function will be updated.

Taking proper care of secrets is important, so I’m using Earthly’s secret support whenever I touch to my AWS credentials. This way I can ensure they aren’t cached.

To call my deploy step I need to pass my aws config files as secrets like this:

earthly \

--secret-file config=/Users/adam/.aws/config \

--secret-file credentials=/Users/adam/.aws/credentials \

+deployAnd with that, I have a container running in AWS, where I’m only billed for the milliseconds it runs, with a full – although simple – deployment pipeline.

Earthly makes CI/CD super simple

Fast, repeatable CI/CD with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.